Lik Ink, based in Hong Kong, went online in 2012.

At that time, owner/operator Andrew S Guthrie realized that he had come across enough independently produced printed matter by individual artists and/or publishers, along with his own artistic publications, to amass a modest online store.

While the internet provided a reasonable overhead, it quickly became clear that it was easier to sell in person, at book fairs, artistic events, or book launches. There was also the matter of what sold, which of course varied from location to location, but more often than not it was that one particular item that the audience endorsed. The listed items here were particularly popular.

Lik Ink never stocked more than five of any particular item, and when inventory went to zero sometimes it took a while, or never at all, to re-stock that title given the nature of artists and their manner of organization (as well as the limits of an edition). Lik Ink can be included in that equation.

Regardless of mass appeal, all of these titles fit Lik Ink’s impetus, and stand as a representation of Hong Kong’s artistic production via independently produced books and zines in the first decades of the 2000s.

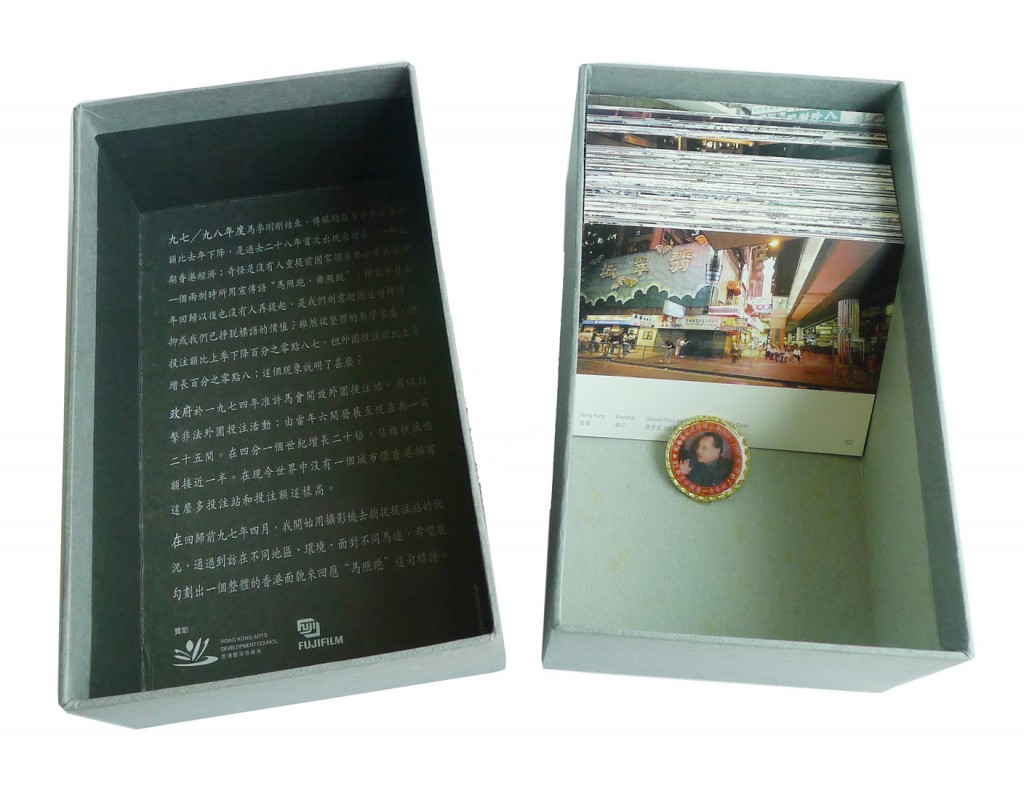

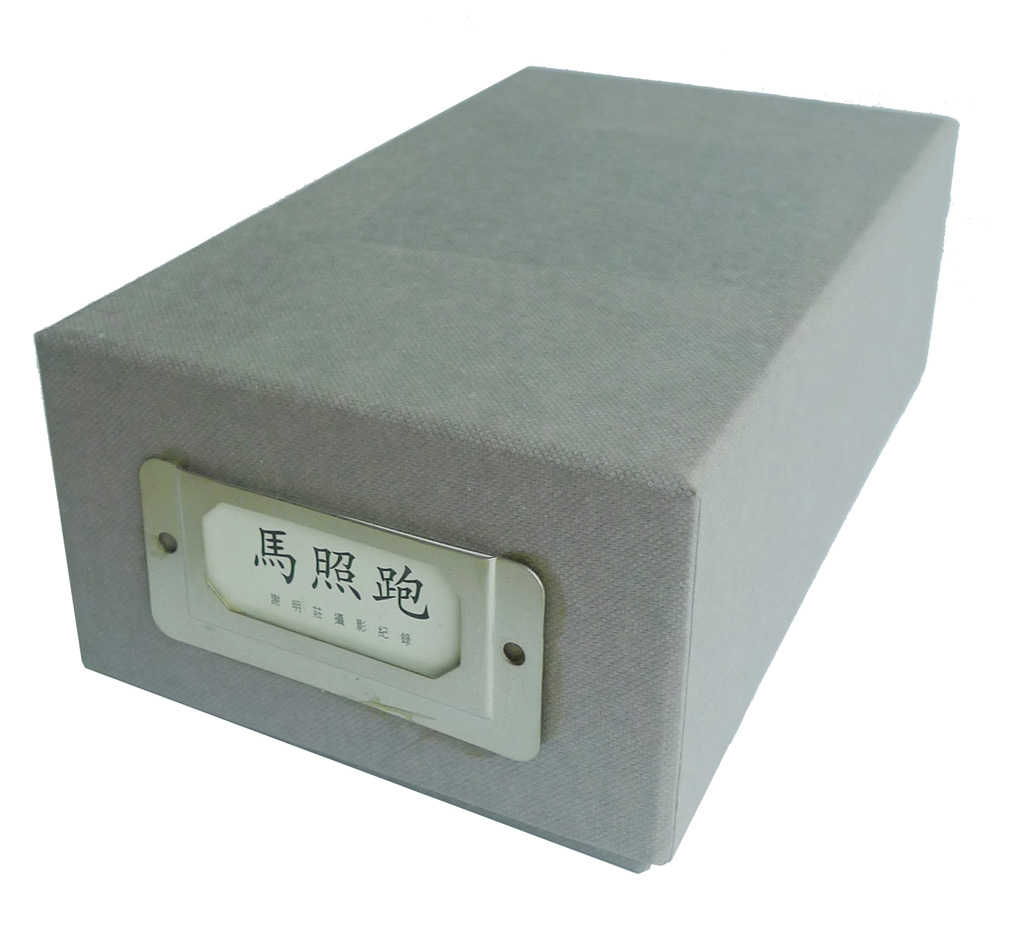

“Horsing Racing Will Continue in Hong Kong” by Tse Ming Chong, self-published Hong Kong in 2000 17cm x 10cm x 6.5cm

The first cannot be classified as “book” or “zine”, more properly it’s an “artist edition”, a self-published artwork by artist/photographer Tse Ming Chong, produced in 2000 in an edition of 300, three years after the handover of Hong Kong to China in 1997.

As to be expected, there was much anxiety as how things would proceed from that point onwards, with Chinese premier Deng Xiaoping making the curious statement that Hong Kong citizens would be able to continue dancing and horse-racing after the handover, as if those were the paramount values and/or pursuits of the majority of Hong Kong citizens.

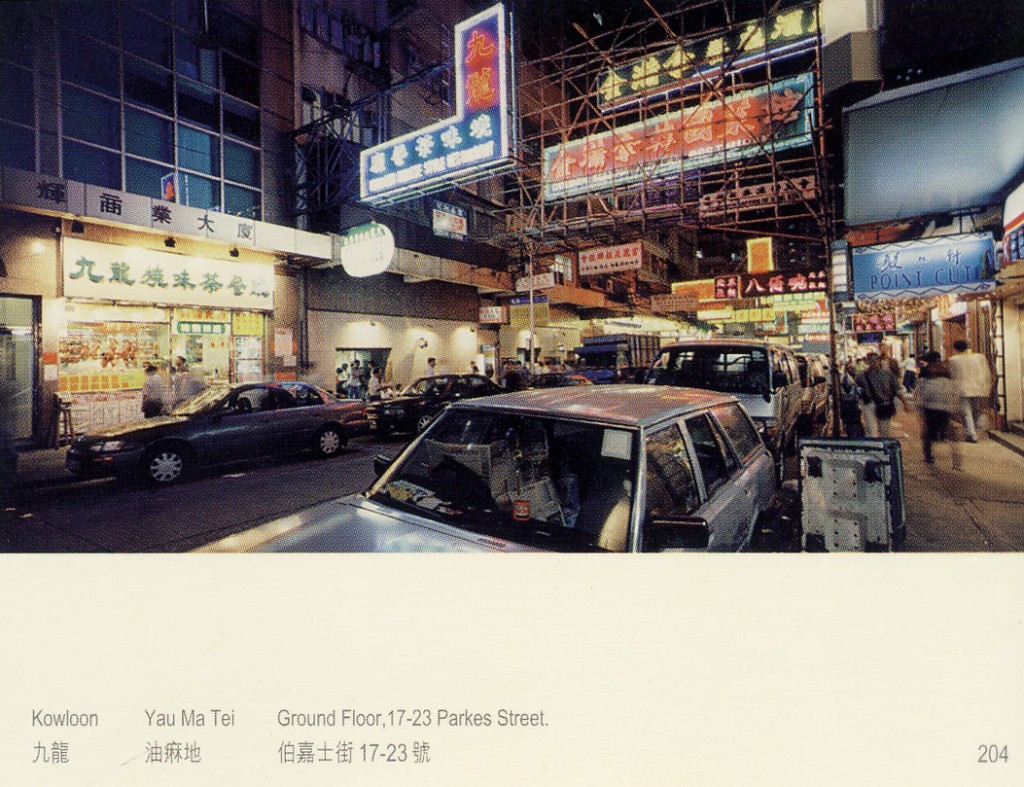

Tse Ming Chong’s edition consists of a box that contains a written explanation of the project, referencing Deng Xiaoping’s curious statement, a lapel button with image of the Chinese premier, and small rectangular cards that show one image of every Jockey Club betting station in Hong Kong and Kowloon, the Jockey Club being one of the city’s huge generators of cash via horse race gambling and numbers games (where bettors try to select a correct combination of sequential numbers).

The project bears the ambiguous qualities of artmaking, addressing the situation without establishing a precise meaning. The obsessiveness of photographing every non-descript Jockey Club (which numbers into a multiple of hundreds) places the project within the confines of “conceptual art” while also implying a “paying of dues”, a humbling pilgrimage undertaken by the fanatic, extra paradoxical considering the profit-making agenda of the Jockey Club.

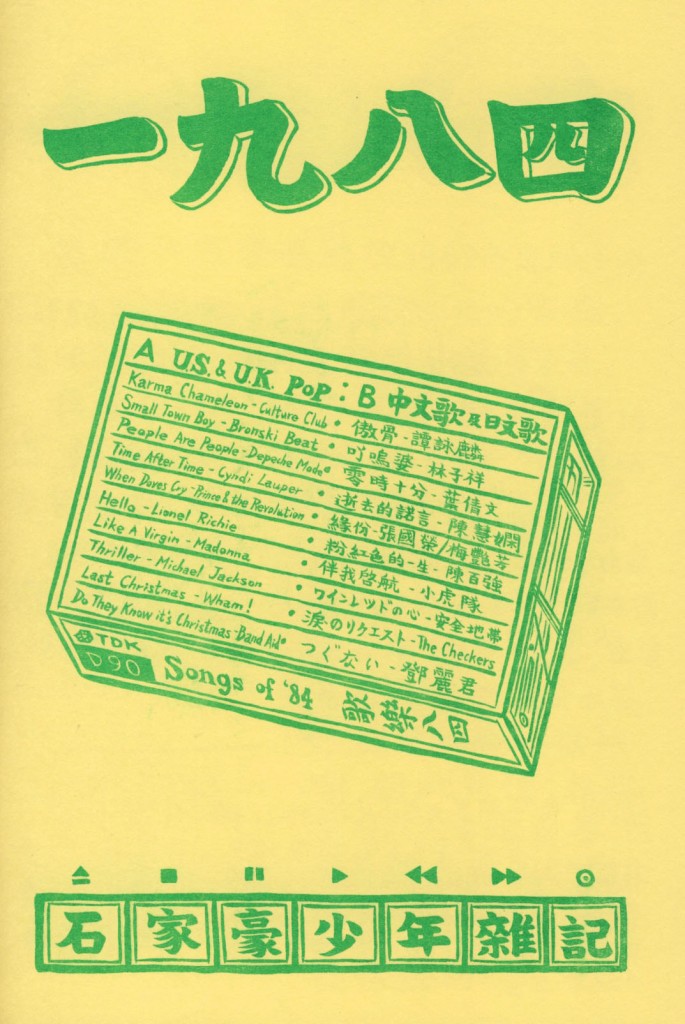

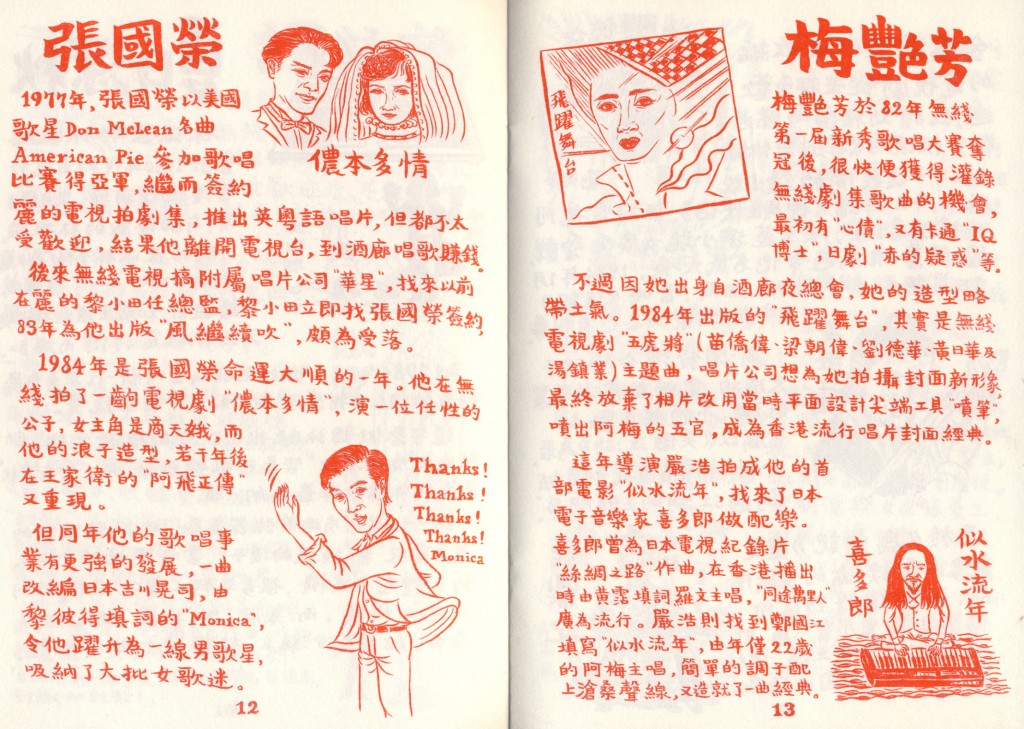

The second project listed here, by Wilson Shieh, is a self-produced zine, handwritten and drawn by Shieh himself, detailing the year 1984 in his own life as well as certain events that took place in Hong Kong during that year. Focusing on “pop culture”, a frequent theme in Shieh’s work, international and Hong Kong musicians and singers as well as movie titles are rendered in Shieh’s idiosyncratic style.

By using a year most generally associated with the George Orwell novel of the same name, Shieh seeks to resonate with that title, distinguishing and differentiating that year in his own life; “1984” by Orwell also ironically entering the realms of pop culture.

Shieh is a well-enough known and successful artist in the city, whose prints and paintings are priced accordingly, but Lik Ink came across this zine, sold for the humble prices of HK$30 at a book fair in Kowloon. The artist himself took on the attributes of D.I.Y. zine culture, sitting on a low stool next to his wares like any of the other vendors.

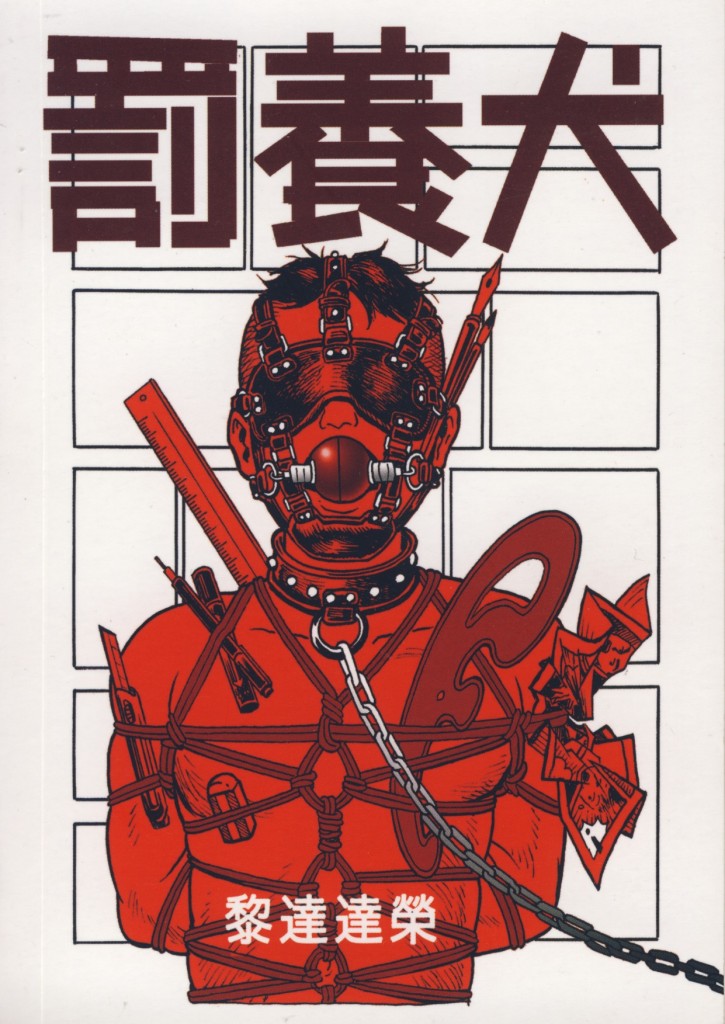

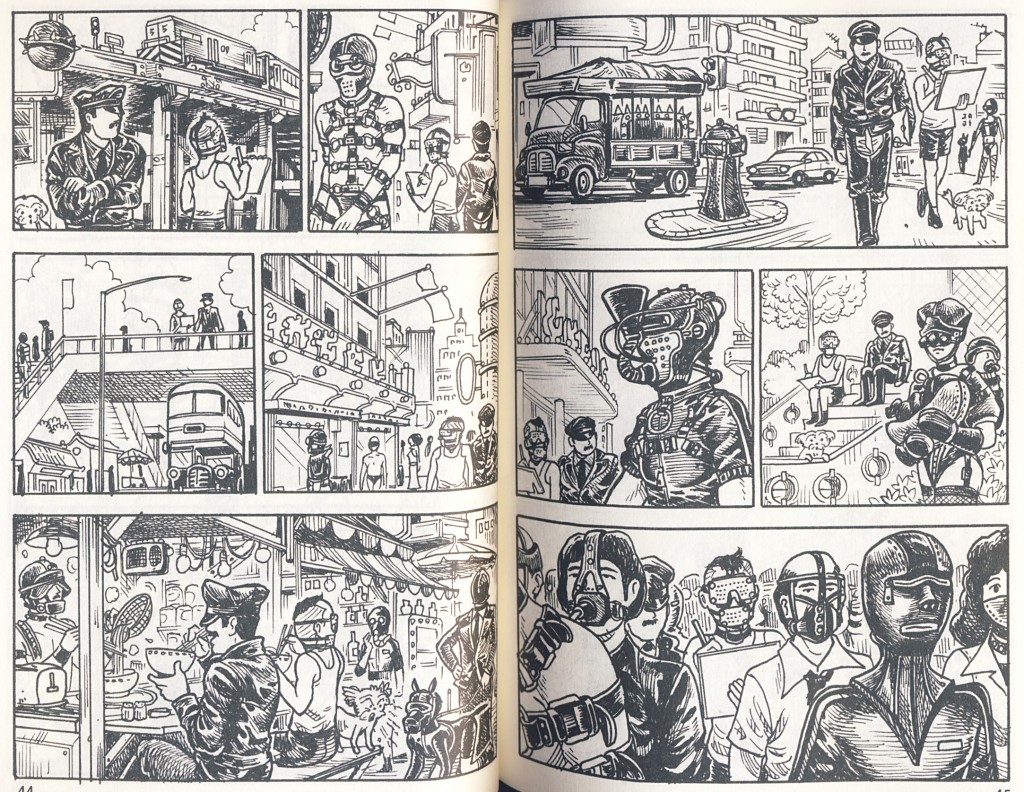

In ” My Dog Can Draw” a young comic book author is unable to find any inspiration. He then meets a bad tempered professional comic artist, and somehow becomes his trainee in comic making, although in a BDSM way.

The final item in this survey is the work of manga or cartoon artist Lai Tat Tat Wing (or 黎達達榮) demonstrating the genre blurring in Lik Ink’s project, as “My Dog Can Draw” is not strictly speaking an artist book or zine. It was the bizarre subject matter and title of “My Dog Can Draw” that drew Lik Ink’s interest.

Tat Wing’s began drawing comics at a young age, inititally photocopying and distributing his work to his classmates. He has freelanced for local and oversea’s magazine and organizations and has received various awards, but his work is distinct within the Hong Kong comics community. For one thing, “My Dog Can Draw” is a wordless recounting of “a ‘comics guy’ adopting a “literati” as his assistant” but this relationship is portrayed as an S&M master/slave relationship, with all the accoutrements (discipline/bondage) of that type. Again, seeing as the story is conveyed without a written word, the comic’s meaning is fluid, with questions about labor/business hierarchies or employee/management interactions implicit in the 2013 self-published book.