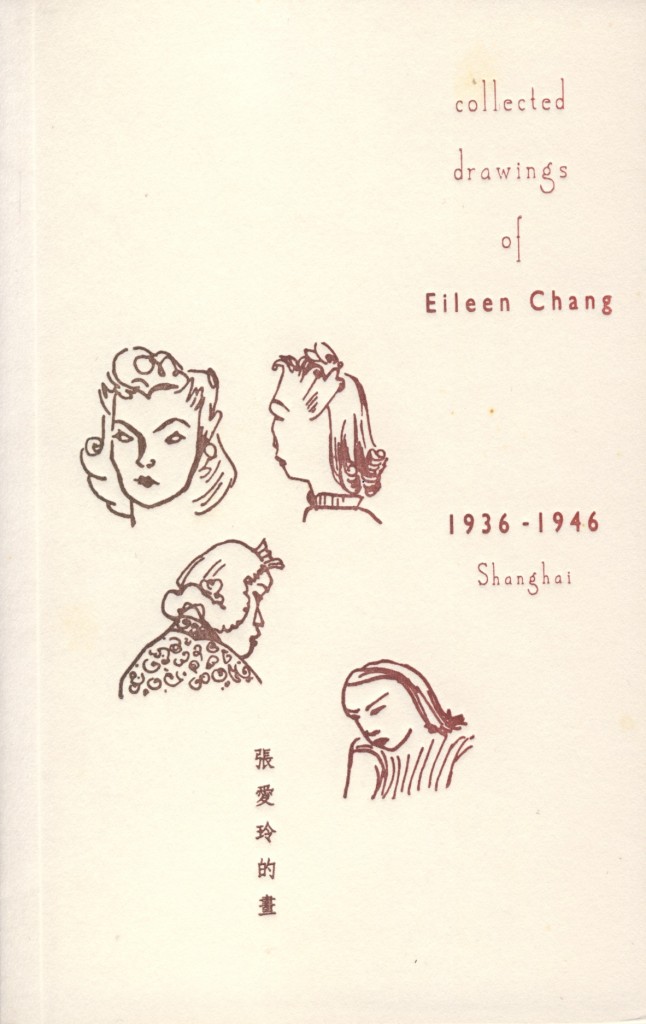

“The Collected Drawings of Eileen Chang 1936 – 1946, Shanghai” was a consistent best-seller, both on the Likink website and when sold at book fares.

First produced in 2003 by Chen Mi Ji Cultural Productions Co. Ltd. for Zuni Icosahedron’s adaptation of Chang’s “18 Springs”, the book went through 3 editions, piles of which I tripped across, one day many years ago, in Chen Mi Ji’s shop in Central Hong Kong.

While demand seems to have entailed 3 editions, by the time I came across the book, there were boxes of the thing stacked in the shop’s back room. At different times, I cut deals for multiple copies until finally Chen Mi Ji was priced out of Hong Kong Island and moved to an industrial area in Kowloon. Even though I was paying for them and then adding a healthy mark-up (which nevertheless saw them sell) a friend informed me that at one point you could walk into Chen Mi Ji and grab them for free. I suspect that the book, in the best of Hong Kong traditions, is a bootleg, that is, it was compiled and printed without the permission of Eileen Chang’s estate.

While I couldn’t precisely say why the book was so popular, Eileen Chang herself is iconic to both Hong Kong and Shanghai, being the author of multiple English-language novels which are located in either city, as well as having been a Chinese and English language newspaper columnist in Shanghai, as well as, as you see here, having been a visual artist (or sketcher). All that indicating the nature of her unique genius at that moment in Chinese history.

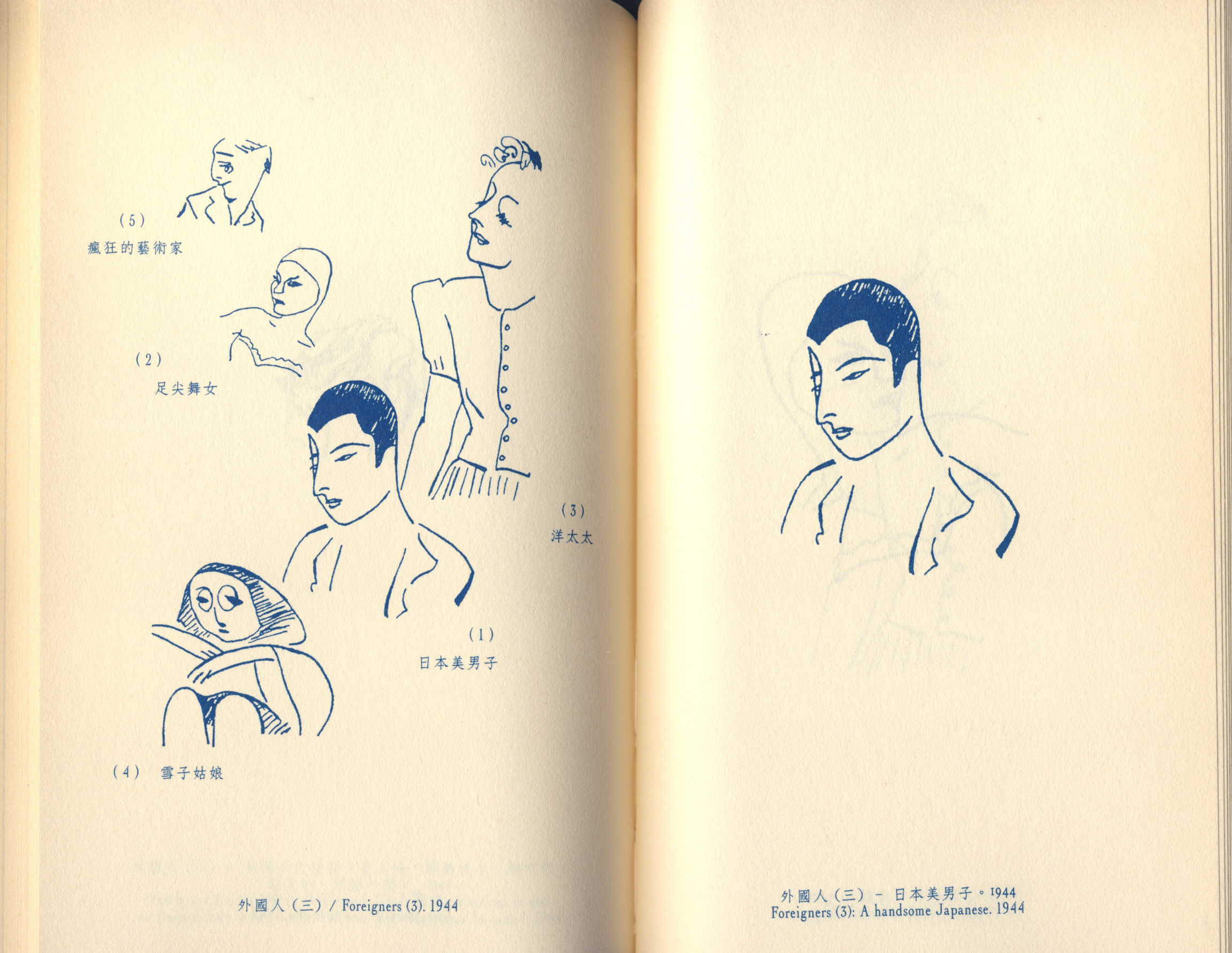

Chang is perhaps best known to western audiences for the 2007 film adaptation of her novella Lust, Caution by Ang Lee, a plot that insightfully details an intense sexual relationship that foregrounds the ethical ambiguities inherent in collaborationism as contrasted with its clandestine resistance (the novella takes place during the World War Two Japanese occupation of Hong Kong and Shanghai).

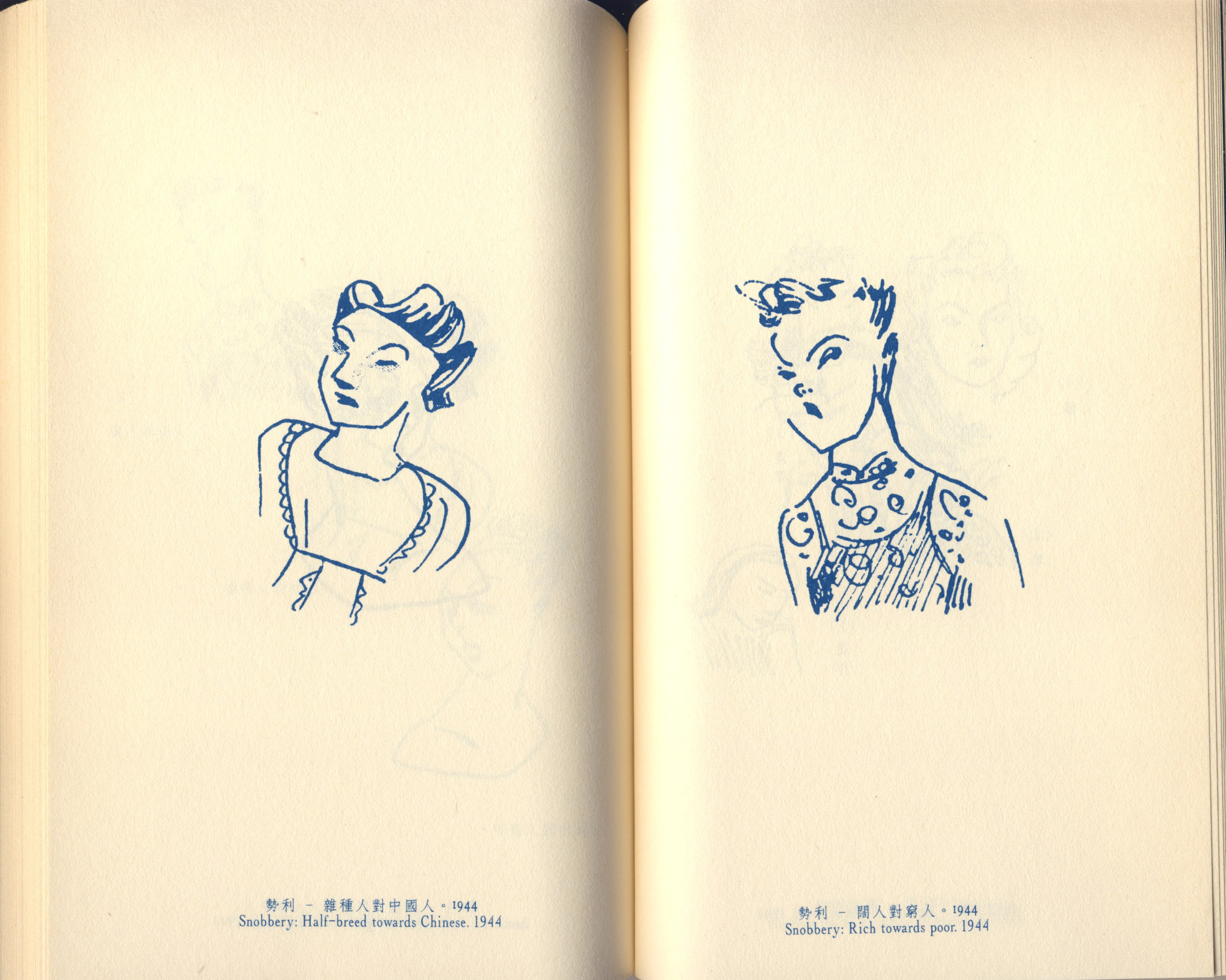

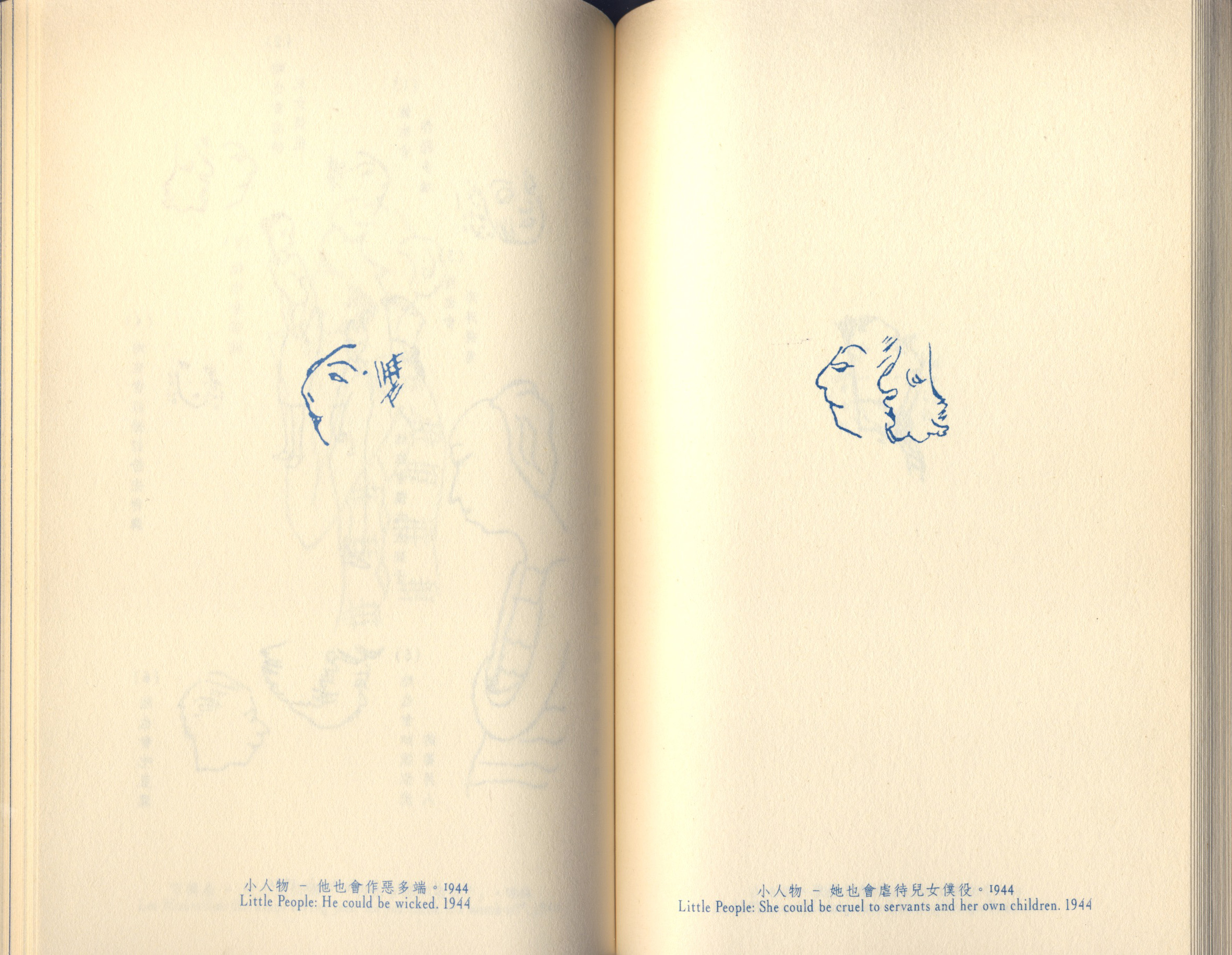

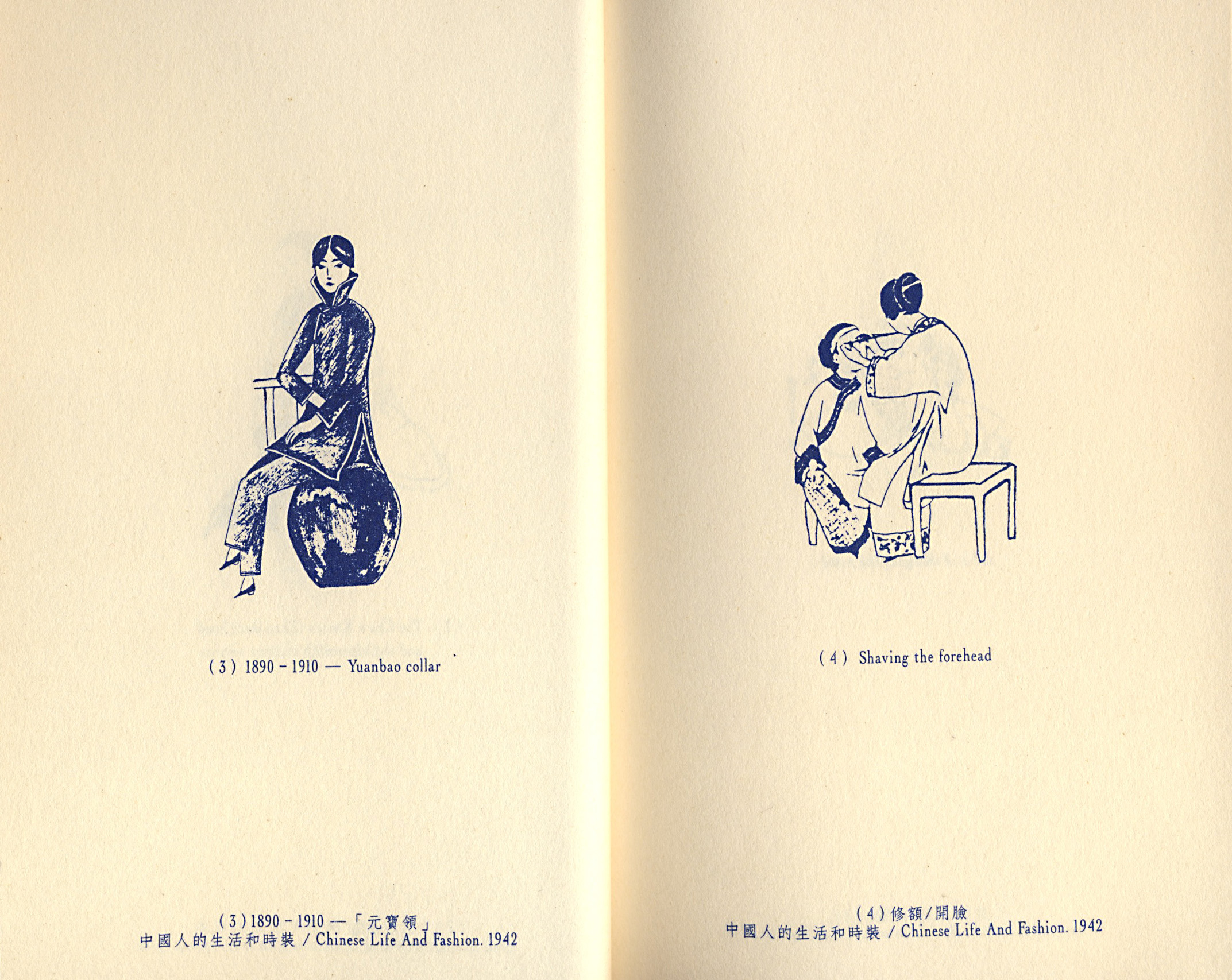

The drawings themselves yet involve Chang’s literary wherewithal, as she pithily documents, through captions and drawings, the high and low cultural and economic milieu of that era’s vibrantly modernist if decadent Shanghai. As such, Eileen Chang stands out as the Chinese “native” who choose to write in English, thus becoming a cultural figure embraced by “local” cognoscenti as well as the “foreigner”. She also embodies, in singular form, what distinguished a multi-cultural colonial Shanghai (and indeed, Hong Kong) from other Chinese cities. All this landing us at the obvious: she was a successful female writer who made her way in the patriarchal confines of a pre-WW2 Chinese/European city.

For further information see this article (link) “How Hong Kong Shaped Eileen Chang” by Ilaria Maria Sala