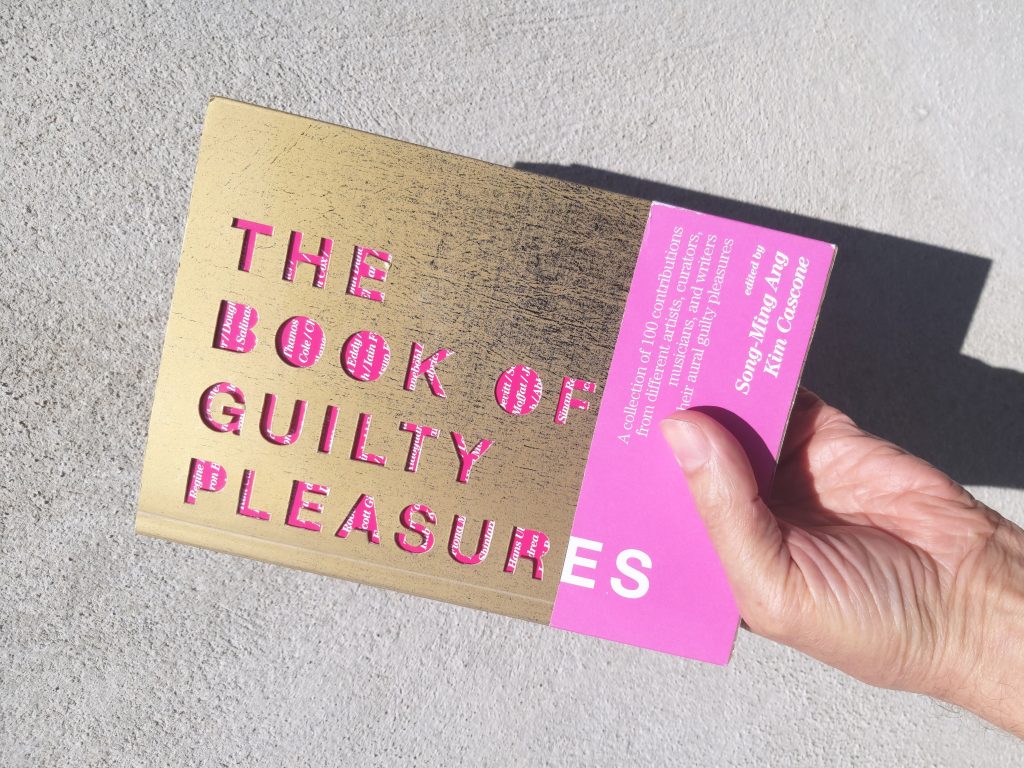

The Book of Guilty Pleasures: A collection of 100 contributors from different artists, curators, musicians and writers on their aural guilty pleasures

Edited by: Song-Ming Ang and Kim Cascone

www.circadiansongs.com

Published 2011 in an edition of 1,000

ISBN 978-981-08-8069-9

Though the title and subtitle say it all, informing you what you’re basically in for, the other information you might want is – what’s the point? It’s a fun and intriguing premise, especially when I came across it at an interactive performance led by one of the book’s editors at Spring Workshop in Hong Kong, where the audience was invited to explicate and then play a song that was purported to be their “guilty pleasure”.

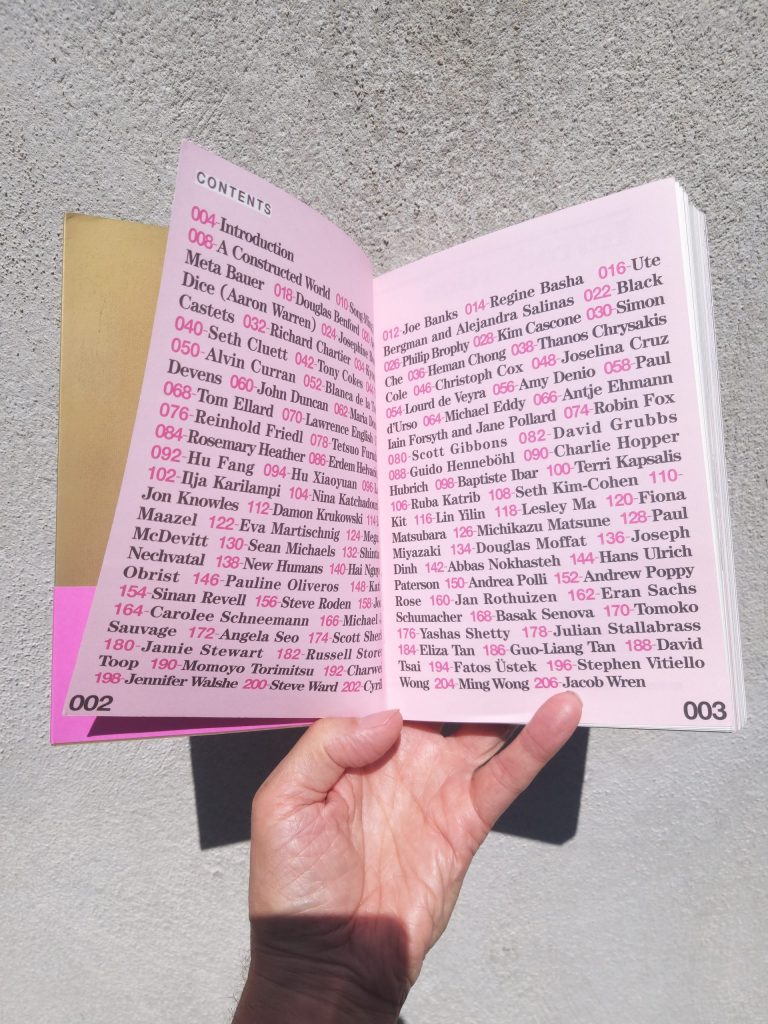

The book, on the other hand, elicits the “guilty pleasure” testimonies of various art world stars, quasi-stars, those on the way to stardom, or those who have fallen off the star-making bandwagon. This includes better-known artists such as Carolee Schneemann and Pauline Oliveros, or curator Hans Ulrich Obrist, as well as 97 other people who you may know well or not at all.

This plethora of artists does serve a tangential but pragmatic purpose – to inform the reader about various artists and their practices, as the editors solicited a wide-ranging and international cast. But the premise is in some ways arbitrary. These artists, curators and critics are not being queried about the specifics of their art practice but about something that, indeed, any one of us could talk about, as well as being considered an expert on said subject. The subject, “guilty pleasures”, being fundamentally self-indulgent.

That’s what I enjoyed when I got up at Spring Workshop and talked about “Give a Little Bit” by Super Tramp. But for me to go into those details here would be, well, self-indulgent. The subject obviously defaults to “taste”, that stickiest of premises as far as aesthetics and the relative importance of any given artwork. And when someone/anyone defends or elucidates what they consider “good” or “bad”, whether it be TV or conceptual art, the listener receives, tangentially, an insight into the speaker’s personality as well as their relative skills of articulation. But unlike an interactive performance, or visual art, The Book of Guilty Pleasures relies on literary wherewithal and the skills of writing. Something that not all visual or auditory artists are skilled at, in lieu of the critic, scholar or poet. So why/how were these informants selected?

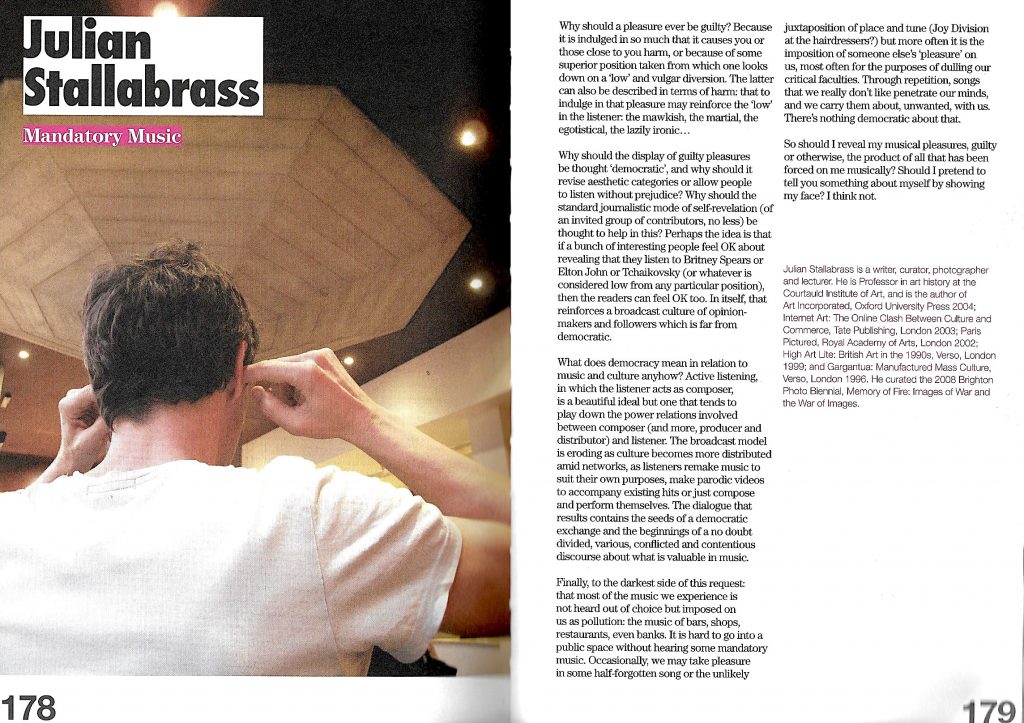

The print project is then a kind of “artist book”, especially in its attractive design, as each artist page is unique, with images that (I assume) were supplied by the informant. The text-based project could be considered “hybrid” literature, in the annals of post-modernism, in its intersections of pop and effete culture. And of course, seeing as the informants are artists or art-related professionals, who are given leeway in the revelation of their guilty pleasure, they can play with the subject (be creative), analyze the premise, or take the piss out of the entire idea.

Witness photo-text-video-audio-sculpture artist Jon Knowles when he says, “When something is expressed as a guilty pleasure in an emphatic non-ironic way it can’t be taken at face value. The supposed irony-free selection becomes a sort of second level connoisseurship. A fairly recent example would be the way Hall & Oates resurfaced a few years ago on too-cool-for-school playlists.” And then later in his essay, “ . . . (a catalog about earth artist Robert Smithson) not only (included) the earth artist’s book collection but a bibliography of Smithson’s photographic belongings, suggesting that an understanding of his work must now included facets of the non-artistic lifeworld. This phenomenon in history making obviously provokes a proto-post-Fordist sense of the intricate weaving of life and work first exemplified by Smithson’s artistic and intellectual opposite Warhol.”

But in point of fact, reading/owning this book might be a kind of guilty pleasure, as for sure, it’s not a weighty theoretical tome (even with something like Knowles’ discourse). It’s bit of a dip-into-the-smorgasbord come-and-go bathroom or just-before-bed kind of book, albeit edited from an “artistic angle”. Some artists, being artists, don’t even stick with the “aural guilty pleasure” of the subtitle, with Seth Cluett broaching the bath or bathwater as his guilty pleasure, Carolee Schneemann revealing her obsession with the TV show Everyone Loves Raymond, Megumi Matsubara talking about her infatuation with watching people write with paper and pen, and Hu Xiaoyuan revealing her habit of listening in on a phone when both parties say goodbye but don’t actually hang up.

But most of the artists stay within the parameters of the “aural guilty pleasure”, the bottomline being that recorded music, pop or otherwise, is something we are now all involved with to greater or lesser degrees, and it is, regardless of relative demographic or genre, a thing ever dependent on “popularity”. A pulp detective novel might be analogous to “guilty pleasure” when placed on the bedside table of John Paul Sartre, but recorded music is now pervasive, unavoidable even, and we don’t feel the same exact need to defend, or stick up for our recorded musical choices as we would be impelled to depose or elevate Existentialism.

Thus, the book also acts as a kind of pop music criticism, casual but at times well-articulated; pop music criticism, whether involved with rock, country, jazz, hip-hop, K-Pop or Afrobeat, being its own kind of pop culture, a thing that can be easily discussed or peremptorily dismissed. The “guilty pleasure” in regards to one’s inexplicable diversion from their taken-for-granted or what-they-are-known-for taste-making usually involves what we vernacularly refer to as “cheese”. It’s cheesy! Or saccharine, or sentimental, or that worst of insults for the cognoscenti, mainstream or formulaic, and by that of course we mean “pop”. But another stand of the “guilty pleasure” involves a taste for music that runs counter to one’s ethics, or the preferred music-maker who expresses abhorrent opinions outside of their role as a music-maker.

Writer/critic Josephine Bosma picks rapper 50 Cent as her guilty pleasure, prefacing her essay by stating, “The only music I have had to defend in my collection is rap music.” Which, in my experience, is typical for the genre; curious given its mega-successful standing in the marketplace, while yet being absolutely reviled by a large swath of the population. Bosma makes a good case for her attraction and repulsion to 50 Cent’s debut album Get Rich or Die Tryin’ with its mainstreaming of “gangster rap” tropes. She says, “I believe 50 Cent’s ‘from rags to riches’, ‘from dirty ghetto to hummer-cum-palace’, ‘from bad boy to filthy rich superstar’ dream . . . I can feel it in my belly when his voice gets sharp, when I just hear how his nose must flare when he spits certain rhymes, when he does not act. Like I, as an atheist, can be convinced time and time again, by any good gospel singer, that there is a God.” But then she adds, “At the same time I don’t believe a word of it. There is a genuine hate and frustration in the rhymes of 50 Cent. He does not care people don’t like him because he has taught himself not to care.”