Just as everywhere (in the so-called western world) had its hippie (who you still occasionally come across, or a hybrid thereof) it seems that everywhere also had its punk (and when was the last time you came across one of those, or a hybrid thereof?)

One can contextualize (or simplify) those circumstances as trends that worked off of each other, the hippies coming about shortly after the post-WW2 economic boom, the punks during the bleak economic downturn of the 1970s.

These were cultural reactions (towards society at large, as well as punk to hippie) which came about due to unforeseen and incongruous opportunities; the point being that while economic and social forces exerted an unavoidable influence (one that sometimes is all-too-conveniently ignored) hippies and punks took advantage of what was at hand, in the punks’ case fostering a term still in wide usage: D.I.Y. (do-it-yourself).

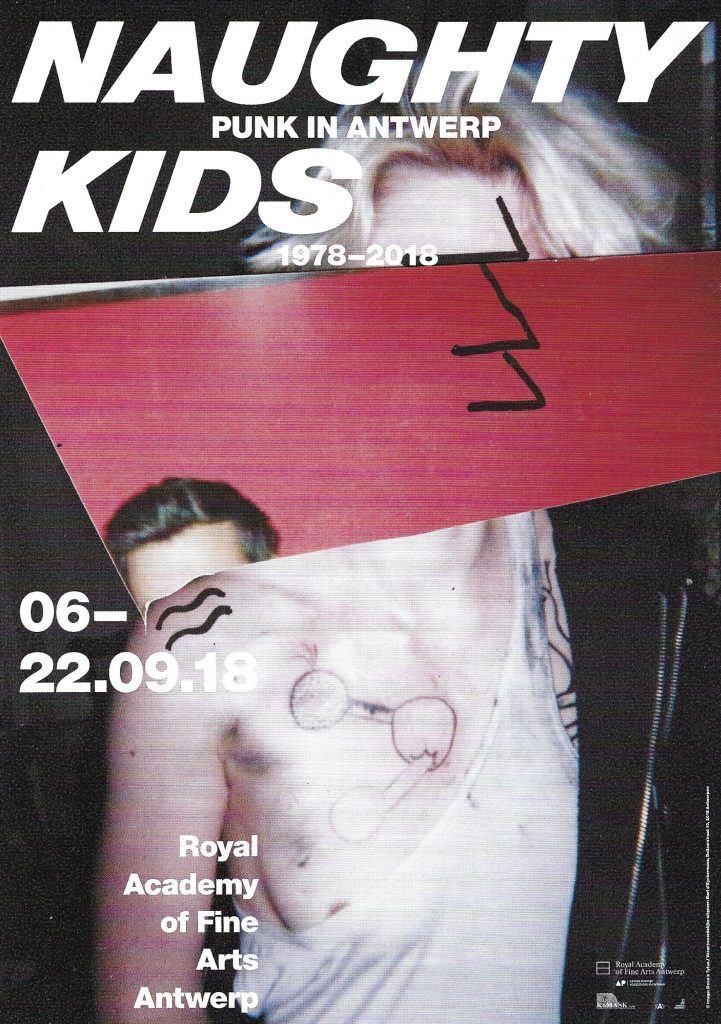

This is an aesthetic as well as a way of life; and those terms (or points of view) become intertwined and/or confused as far as a “belief system” or ethic. Of course punk was fundamentally nihilistic and dismissive of “beliefs” beyond poking you in the eye (or being “shocking”), but we recognize punk (as can be easily noted in “Naughty Kids: Punk in Antwerp 1978 – 2018”) by its slap-dash, provisional and anti-professional approach, both in terms of graphics and clothing as well as music (its driving force).

Punk, as “youthful explosion” is long past. It was my WW2, and I mean to say that it now bears the same temporal distance to younger people as WW2 did between my father and myself. Yet it seems to have far more contemporary relevance than, say, Glenn Miller. The paradox being that punk’s aesthetic concerns, or dis-concern, might have been a breathe of fresh air (though it stank) but it was most assuredly of the moment, and I doubt its adherents expected to turn up in an exhibition at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts Antwerp forty years after the fact. The world was supposed to have ended by now.

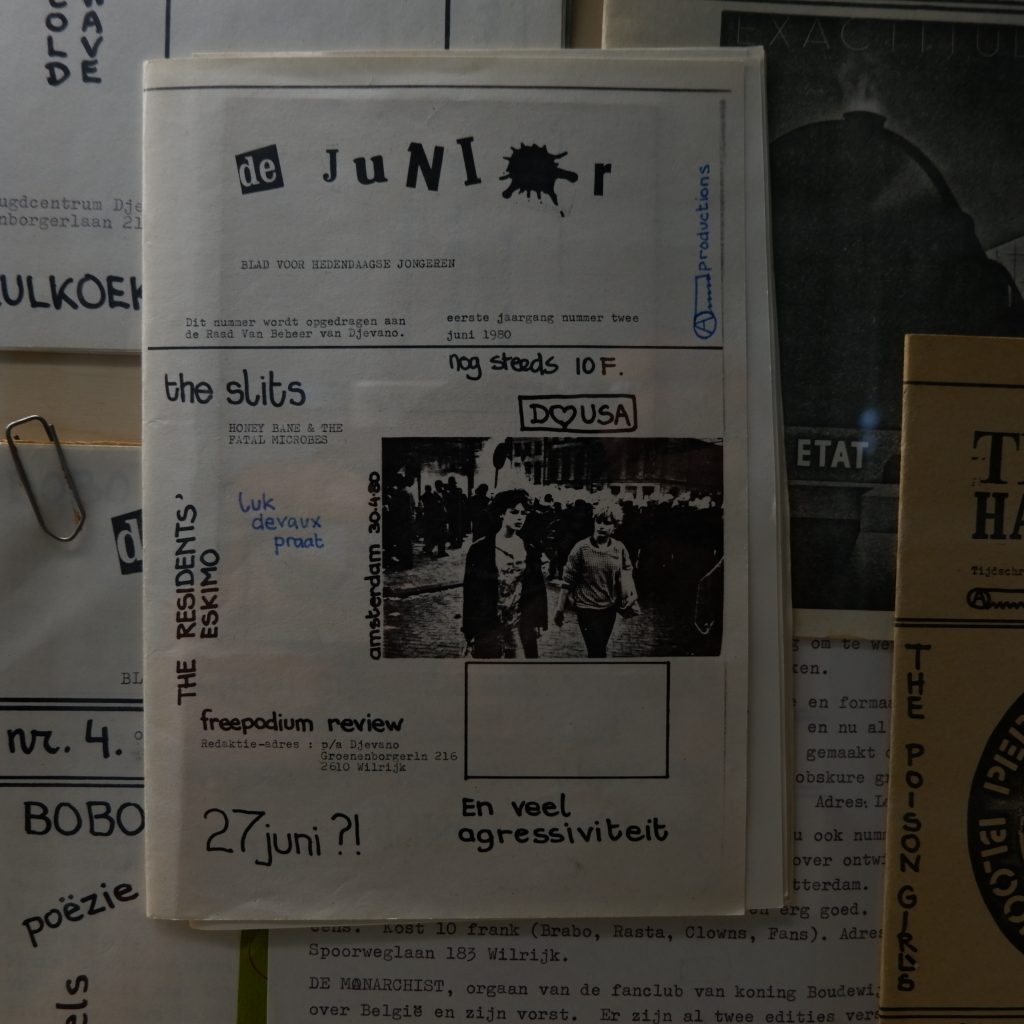

It is the archive that has been built up, squirreled away, and then gathered together (curated); surely all aesthetic symptoms of our era. All these scrappy, fragile, D.I.Yed artifacts are relegated to the vitrine. We can’t, or shouldn’t (en masse) handle them, even though, back then, they might have been thrown away without a second thought.

“Naughty Kids: Punk in Antwerp 1978 – 2018” sidesteps some of these inherent paradoxes by having multiple recordings and videos playing simultaneously, providing the exhibition space with the appropriate cacophony. Seeing as I am not fluent in Dutch (as of yet), I still gathered that the retrospective is thorough, providing videos of disparate performance spaces, an abundance of “zines”, stacks of cassettes, newspaper articles, posters, photographs and pieces of clothing.

Viewers were supplied with a zine-like bi-lingual (Dutch/English) “visitors guide” attributing the exhibition’s objects (like any good exhibition catalog is wont to do). The guide utilizes a “punk aesthetic”, but its mimics rather than makes-do. It is deliberately slap-dash rather than necessarily low-budget. It even goes so far as to state (on its last page) “PUNKS DON’T NEED EXHIBITION GUIDES” Then who does?

The “guide” also includes a mission statement (of course) that reverts to the unavoidable (computer) desk-top publishing mode (uniform font, spacing, columns) an organizing method punks were bereft of, and makes this rather extraordinary statement, ‘The punk movement . . . was the last subculture to leave its traces in different artistic fields.”

Who influenced what and how, is far from a monolithic proposition, and while punk, or its outshoot “hardcore”, aspired to a kind of purity, it will forever be distanced from rectitude. It was a youth movement, and all that implies in the marketplace. “Naughty Kids: Punk in Antwerp 1978 – 2018” tries to trace “the last subculture to leave its traces in different artistic fields” by way of later day “punk fashion” and the artworks of well-known Belgian artists, such as Jan Fabre, Guillaume Bijl and Narcisse Tordoir, but the whiff of Dada was already upon us, just as Hip Hop instinctively but unknowingly appropriated appropriation.

To be truly, or pretend, punk (and/or dada) why not steal one of the exhibit’s best knockoffs? And despite the catalog I am unsure who to attribute it to, but it might be by Jan Fabre, so it might constitute a “famous artwork” but it’s #1: practically worthless, and #2: a difficult theft. It’s a pair of cement shoes, a thing applied by the mafia (or a similar organization) to a victim’s feet before he or she is pushed off the dock into the harbor. Such a prank allows for the theft of an artistic re-creation of a criminal’s throwaway creation and that Antwerp is a harbor currently permeated by mafia smuggling rings. It’s iconoclasm that ties all that together, a ready ingredient of punk. But in a show meant to honor punk?

Despite my cynicism, which in this case seems practically de rigueur, I couldn’t say I was unaffected by the implicit enthusiasm of yesteryear’s punk rockers and their disheveled artifacts, and of course, my own mnemonic reactions to that era.

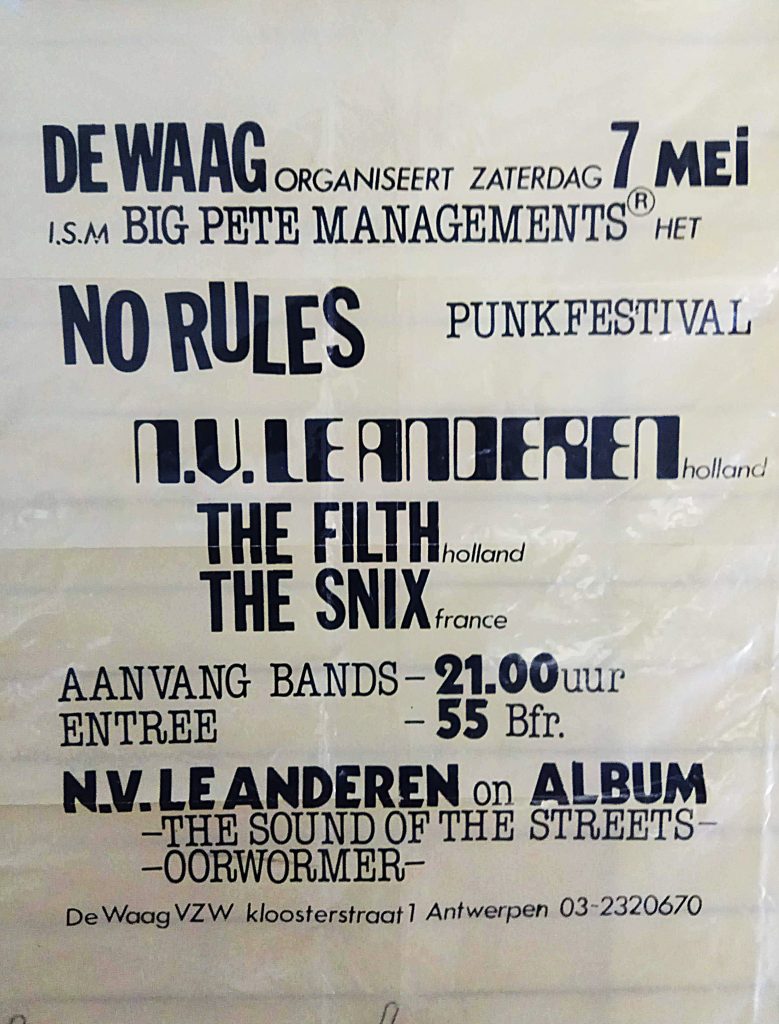

The viewer does get a feeling for the city as it was then and how it has changed, along with a direct primer about Antwerp punk and its impure and/or sincere aspirations. Much of this is scattered like clues (a secret history?) around the exhibition and relies on the intrepid visitor to investigate further. For instance, a poster advertising a punk show at De Waag not only displays the creeping influence of “professional management”, but an obscured reference to some of punk’s political inclinations. De Waag was not only a “youth club” but was associated with a hardcore anti-fascist organization; at one point, the target of a fire-bombing.

Seeing as aesthetics as opposed to ethics is perhaps the more direct outcome of punk, and that its politics were at times confused if not retrograde, this leaves many of its productions up for grabs. Punk is often credited with a blending of high and low culture, of embracing the dumb as well as the savvy, and boiling it down to a two-minute two-chord attack. All fine and good, if not carried over from Dada and the despised hippie. One is left with the ambivalence of “selling out” or making a career out of punk (just as The Ramones intended). In Belgium’s case “The Kids”, who I was previously unaware of, had their first album released and distributed by the mega-corporate Phillips Records.

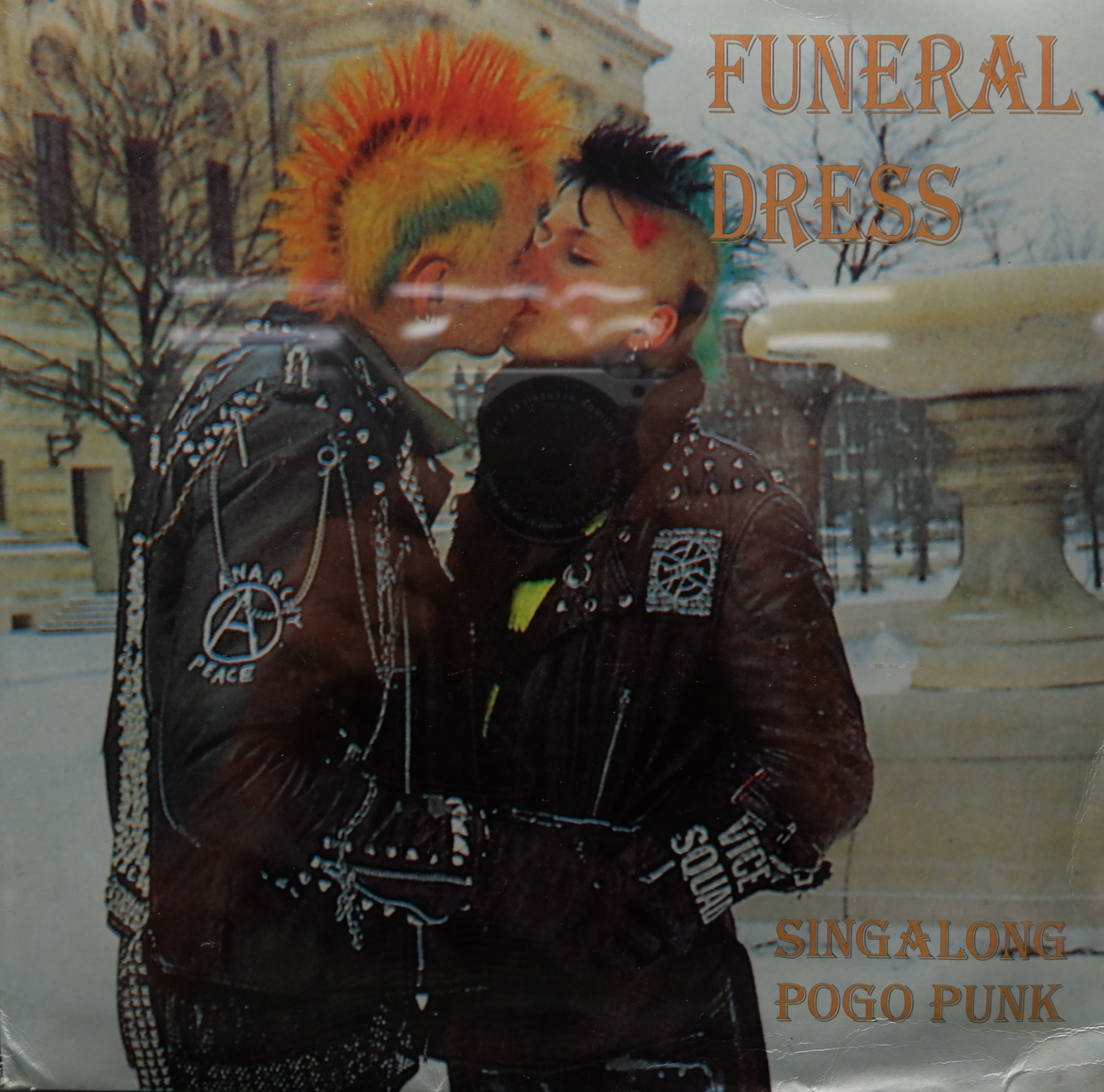

I don’t have a problem with that. I have a problem with fascists. But where that begins and ends, I’m not sure. So, I’m also ambivalent. This is why art can be so powerful; it can elicit a visceral reaction while remaining ambiguous. Perhaps this is why I laughed out loud when I saw the “Funeral Dress” record cover as displayed in a vitrine at “Naughty Kids: Punk in Antwerp 1978 – 2018”.