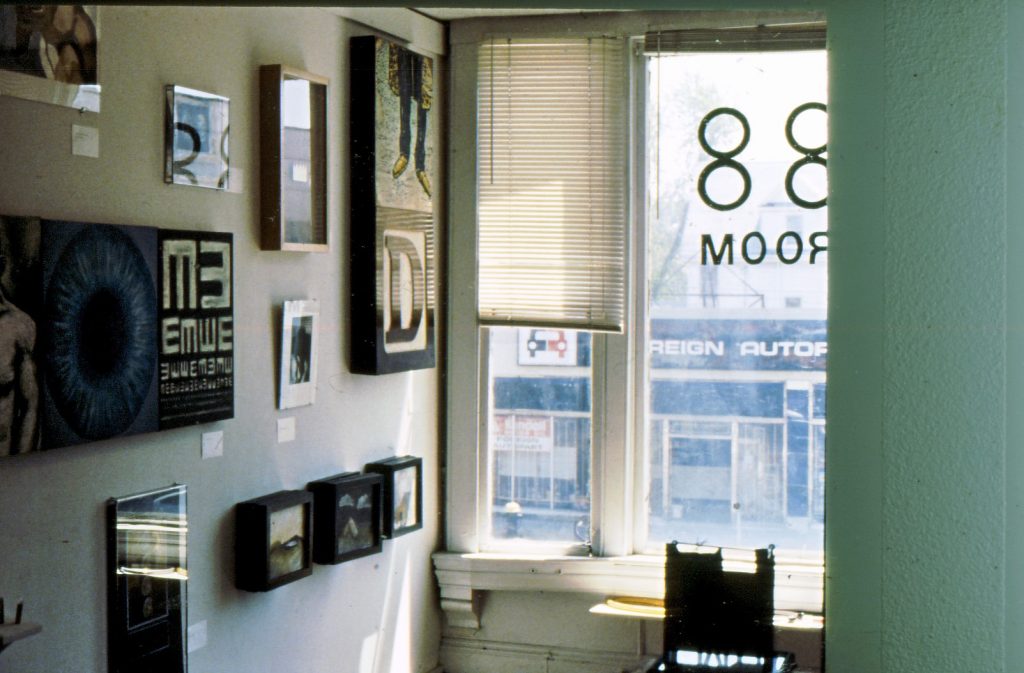

The 88 Room was an visual art exhibition space located in Allston, Massachusetts, a part of Boston across the Charles River from Cambridge, Massachusetts, a district associated with cheaper rent and/or co-housing for transient university students. The 88 Room was able to exist within those affordable parameters for ten long years, perhaps hitting its heyday in the early to mid 1990s.

The 88 Room was specifically located at 107 Brighton Avenue in Allston, in a curious, somewhat dilapidated, almost-100-year-old two-story building. The gallery was on the second floor where a grand hallway could be reached by a street level staircase; a large area surrounded by smaller rooms, probably originally designed for offices of one kind or another. This area came to be known, somewhat ironically, as “the Allston Mall” (click on the name to go to a Wikipedia entry about said mall).

Being a “alternative space”, run on D.I.Y. initiative, in-kind labor and (for the most part) self-financing, the 88 Room struggled to gain mainstream media attention, while yet being acknowledged and appreciated by the wider arts community and its acolytes, in particular the students who attended Massachusetts College of Art and the Museum School (then affiliated with the Museum of Fine Arts).

Nevertheless, the 88 Room did receive a credible amount of print media coverage which was recovered from a storage space in February of 2023. The years covered in these articles represent the pre-or nascent internet era, when coverage of this kind was vital. What you find below also amounts to a critique of said media and how its content is positioned and presented to the public. And while reviews, publicity and such were important for the morale of the 88 Room, this archive now constitutes a record, a bulwark against the erasure of these kind of initiatives, a circumstance all-too-well known in the annals of history.

The print media archive is presented chronologically by date.

June 3 1988, The Boston Phoenix (article by Becky Batcha) “The Economy Show” (group show)

(for a scan of the original article go here)

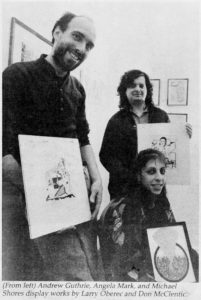

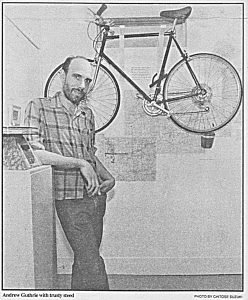

Out of the gate, the 88 Room receives an expanded listing for one of its first shows in Boston’s weekly (now defunct) newspaper, in a show admittedly meant to appeal to the masses: “The Economy Show”, a group show in which all art was priced $75 or below, a concept that perhaps went against the gallery’s non-commercial impetus, which would be better established in the coming years after Andrew Guthrie (the owner/operator of likink.com) took over from co-conspirators Angela Mark and Michael Shores.

Seeing as visual art didn’t translate well to black and white print media, frequently the news source would ask for an image of the front man/woman, an awkward situation or not-to-the-point of the egalitarian or conceptual ambitions of the 88 Room. The caption here also unfairly highlights certain artists to the detriment of the rest of cast. Let alone that the article leads with a cringe-worthy headline: “FOR THE PAINT AT HEART”

Seeing as visual art didn’t translate well to black and white print media, frequently the news source would ask for an image of the front man/woman, an awkward situation or not-to-the-point of the egalitarian or conceptual ambitions of the 88 Room. The caption here also unfairly highlights certain artists to the detriment of the rest of cast. Let alone that the article leads with a cringe-worthy headline: “FOR THE PAINT AT HEART”

In blurb-heavy prose, the short article also states: “At these prices, you won’t snare any sure bets; your artist may prosper (and you with him), or may fade away without notice.”

April 1990, Art New England (article by Rachel Weiss) “Unknown New York” (group show)

(for scan of the original article go here)

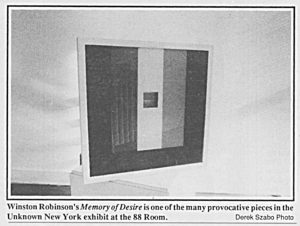

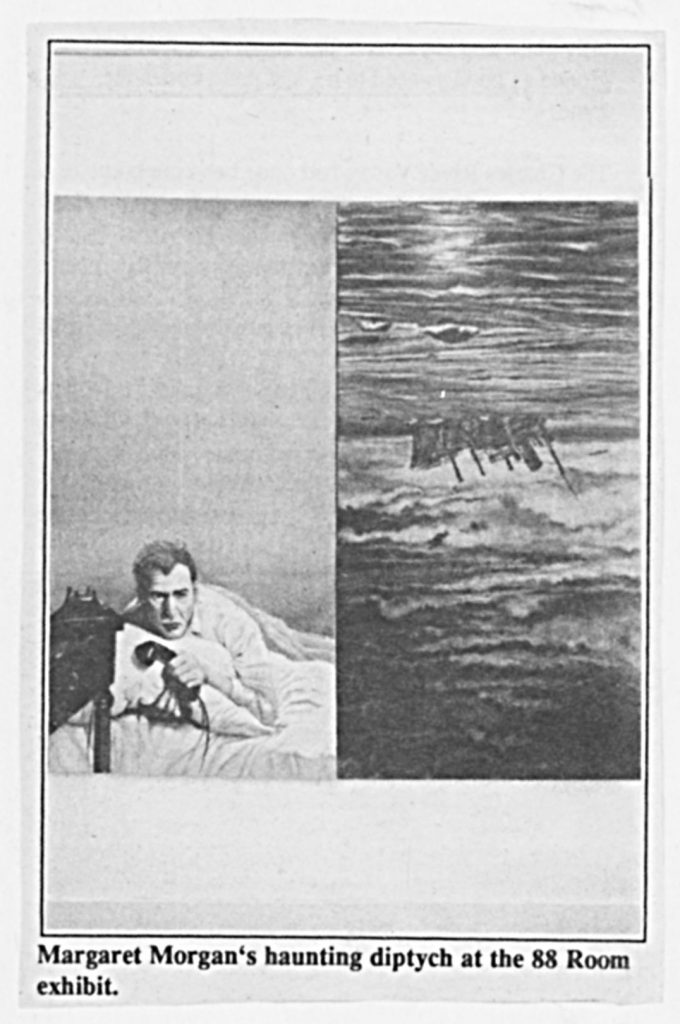

Art New England was Boston’s monthly journal of note as far as arts reportage in a city hardly known for its art market or gallery scene; might as well go to New York City. Which was done in reverse, in a show curated by Winston C. Robinson (R.I.P.) consisting of lesser-know artists from that art-centered city, titled “Unknown New York”

While begging for recognition from such an established source, Art New England itself was judged to be rather staid by the 88 Room. Someone like the author, Rachel Weiss, was probably trying to find her footing as a theoretical or alternative-leaning critic in line with initiatives like the 88 Room, and was kind enough to finally put the 88 Room on Art New England’s beat. But this comes at the price of being, aptly for the most part, critical of the show’s premise.

While positively singling out the work of Hilary Kilros, Magda Dajani and Baron Claiborne for their political/cultural impetus, whose ” . . . works are critiques not so much of the entire cycle of racist or hegemonic attitudes, as how these attitudes are purveyed in the art market”, Weiss also snipes at fellow critic Laura Cottingham who wrote an essay for the show’s brochure (which was considered a part of the show by Robinson) saying, “Her observations about the mechanisms controlling the distribution of art are couched in a tired anger, noting the lack of an effective activist response without actually envisioning or calling for one.”

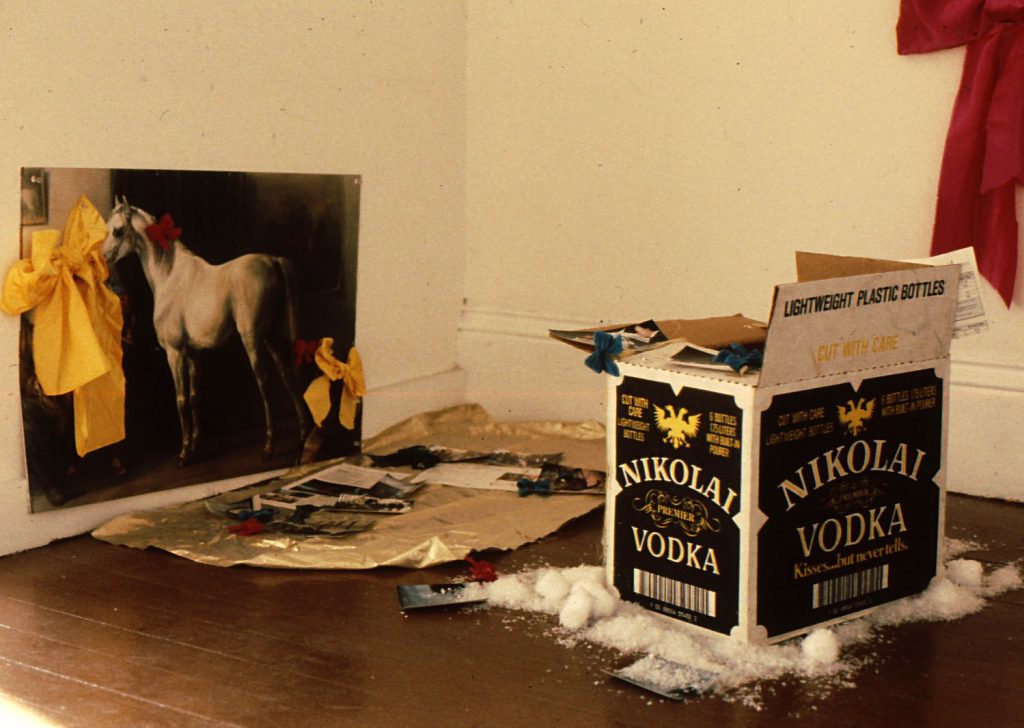

As you can see, in the links provided above, some of the participants in the show eventually became slightly less unknown or entirely well-known, but what’s noteworthy and entirely absent from Weiss’ review is the work of Karen Kilimnik, whose work in “Unknown New York” was quite edgy in terms of its execution, to the point of being greeted by a “wtf” by most visitors to the gallery, artist and non artists alike. Kilimnik, most unexpectedly, has gone on to be the most successful artist in Robinson’s survey.

Installation shot of Karen Kilimnik’s work in “Unknown New York”, referred to at that time as “scatter art”. A cheap reproduction of a painting of a horse, ribbons, fake snow and a box that vodka came in.

January 11 1990, Allston-Brighton Journal (article by Beverly Creasey) “Unknown New York” (group show)

(for scan of the original article go here)

This article is posted out of chronological order to provide a contrast to Weiss’s biting critique of the same show. The author in this case, Breverly Creasey, is entirely positive, even effusive. The contrast is also provided by the source, a small weekly newspaper that served Allston-Brighton (a long-gone circumstance) as well as Creasey making 88 Room part of her regular news-gathering circuit (as you will note below).

Creasey quotes from Laura Cottingham’s essay that was included in the exhibition: “What use is it to free art from its own critical orthodoxy only to deliver it to the demands of the market?”

Creasey quotes from Laura Cottingham’s essay that was included in the exhibition: “What use is it to free art from its own critical orthodoxy only to deliver it to the demands of the market?”

Taking into account that the 88 Room was certainly positioned far from any kind of commerce, and exhibited of-the-moment art free of charge, the paradoxes of Weiss’ critique should be taken into account, just as Creasey’s comment that Cottingham’s essay should be “nailed to the doors of so-called Art Cathedrals of Leo Castelli and Mary Boone, a la Martin Luther” might be going a bit too far too far in the other direction.

June 14 1990 Allston-Brighton Journal (article by Beverly Creasey) “Post-Hype” (group show)

(for scan of the original article go here)

see link for full article scan (below date, source, show title) for more information about this piece

This is the second of three shows curated by Winston C. Robinson for the 88 Room (the third “Without a Notion” in 1992 went unreviewed). “Post-Hype” was also, for the most part, a survey of New York City based artists (where Robinson was living at the time). This time, Creasey quotes Robinson directly, who explains the show’s title as running counter to the heady critiques of the day, ” . . . for post modernism to become more than an umbrella term for![]() various ideological concerns and practices, its theorists must look beyond the deluge of informed opinion, theoretical posturing and stylistic convenience . . . “. This was the era of concept as well as theory, with much confusion engendered by the term “post-modern”, as it was being continually applied to contemporary art practices, leaving some artists feeling left behind or otherwise behind-the-times.

various ideological concerns and practices, its theorists must look beyond the deluge of informed opinion, theoretical posturing and stylistic convenience . . . “. This was the era of concept as well as theory, with much confusion engendered by the term “post-modern”, as it was being continually applied to contemporary art practices, leaving some artists feeling left behind or otherwise behind-the-times.

But Robinson gets cheeky (as quoted by Creasey) reverting to art’s inherent sensuous qualities, as opposed to the dry circumstances of theory: “What Post-Hype is about, Robinson says wryly, is “standing outside the umbrella and getting wet”; a line as confusing as any theoretical statement, but definitely more playful.

March 29 1990 Allston-Brighton Journal (article by Beverly Creasey) “How People Live”

March 29 1990 Allston Citizen (article by Mark Merchant) “How People Live”

(for scan of article from Allston-Brighton Journal go here, for scan of article from Allston Citizen go here)

This was an idea borrowed from, and approved by Group Material that seemed in line with the 88 Room’s ambitions, while also pointing to the tenor of the times (as far as visual arts) which mixed activist or politically engaged art with conceptual art with street art or graffiti, all trying to broaden the parameters of the so-called “art world” to include under-represented people and spaces as well as opening up what was, is, or could be considered art.

The idea was to collect the objects “ordinary people” lived with, representing their choices and aesthetic as an aspect of art production, while also diverting the museum or gallery’s impetus towards a personal and lived-in spaces. The problem being (if we can call it a problem) that Group Material was an activist collective while the 88 Room was, well, just Andrew Guthrie, as well as Allston being an entirely different kind of neighborhood than the Lower East Side, N.Y.C. (where Group Material was operating at that time). On the other hand, Doug Ashford of Group Material, who Guthrie talked to by telephone before organizing this show, was pleased that someone else had pick up the ball at the behest of Group Material’s effort.

April 25 1991 Allston-Brighton Journal (article by Beverly Creasey) “4 Questions” (group show)

(for scan of the original article go here)

Continuing on from publicly-engaged art practices and attempts to suspend the vagaries of taste, this show’s concept entailed a first-come-first-served open call to any and all artist as long as they answered four questions about art, its meaning and its purpose, the answers of which were posted on the wall outside the gallery space, with the individual artist’s chosen piece hung inside the gallery. The questions were: #1 Where and under what conditions should an artist be shown? #2 How should an artist gauge success? #3 What’s the artist’s responsibility to his/her audience? #4 What does art do?.

While the “How People Live” show (above) required a lot of footwork, solicitation and downright begging, “4 Questions” saw the gallery crammed with the creative community’s over-abundance. The impetus for “4 Questions” necessarily entailed community-building and dialogue, but artists can be touchy, with one individual complaining about the space his piece was allotted, another speculating that the exhibition was a “charity show”, and yet another being told by a high-brow gallery that it would be bad for her C.V. to join such an exhibit.

The full article was a three show review, including “4 Questions”, “An Education of the Heart” at the Boston Visual Artists Union with an animal rights theme (co-sponsored by the Coalition to End Animal Suffering and Alliance for Animals), and a Rosemary Trockel retrospective at the Boston Institute of Contemporary Art, of which the reviewer casts the 88 Room show in much better light. Quote (apropos Trockel): “Her esoteric references are so far “inside” that you need a guide to explain the joke.”

January 10 1991 Allston-Brighton Journal (article by Beverly Creasey) “He Always Ran As Fast As He Could” (solo installation by Deborah Davidovits)

(for scan of the original article go here)

In this article, we get an insight into the “Allston Mall” as well as the artistic potential of Allston, with three shows being reviewed in one. The building at 107 Brighton Avenue (where 88 Room was located) was enticing to anyone with a limited budget and creative or entrepreneurial ambitions. The article notes that the building also served as an artist’s studio and, at that time, another gallery, The Naked Eye gallery, which was attached to a weekly open mic music event that utilized the huge central hall. The 88 Room still gets precedence from Ms. Creasey, if Davidovits’ show could have benefited from a lengthier interview.

The 88 Room usually invited specific artists, rather than issuing open calls, didn’t charge artist fees of any kind or require the artist to watch the gallery during opening hours. Nevertheless, the 88 Room had a focus, a curatorial bias, if you will, which usually didn’t include solo painting exhibitions, a curatorial bias “4 Questions” tried to ameliorate. Thus, Davidovits was “discovered” by way of an installation Guthrie came across at Massachusetts College of Art (where she was going at that time), and was invited to do a show at the 88 Room, highlighting the gallery’s interest in conceptually themed group shows, non-traditional materials and/or installation work. Davidovits was also given free reign, as long as she returned the gallery to the state it was in before her show.

The 88 Room usually invited specific artists, rather than issuing open calls, didn’t charge artist fees of any kind or require the artist to watch the gallery during opening hours. Nevertheless, the 88 Room had a focus, a curatorial bias, if you will, which usually didn’t include solo painting exhibitions, a curatorial bias “4 Questions” tried to ameliorate. Thus, Davidovits was “discovered” by way of an installation Guthrie came across at Massachusetts College of Art (where she was going at that time), and was invited to do a show at the 88 Room, highlighting the gallery’s interest in conceptually themed group shows, non-traditional materials and/or installation work. Davidovits was also given free reign, as long as she returned the gallery to the state it was in before her show.

The 88 Room was community-building in the sense of the connection and social life provided in and amongst the artists who were exhibited. A circumstance that led to a reconnection with Deborah Davidovits, 30 odd years after the fact. To an inquiry via email for further information about the show, Davidovits responded: “In retrospect, the show was not so much a tribute to Ben the Dog, as it was an exploration/investigation of what it means for something to have existed. In gathering into one room all of the objects that were associated with Ben (leash, collar, dog bowl, half chewed bone etc.) as well as all of the memories that my family and I could come up with….. did we succeed in conjuring Ben? Would someone who had never met him “know” him on some level? Do the contents of the room prove, verify, authenticate, on some level, his existence? Well who knew that these sorts of questions would fuel the next three decades of art making and poetry.”

October 1 1991 The TAB (article by Gary Kadet) “Another Thing” (group show)

(for full scan of article go here)

In this phase there were three galleries (The 88 Room, The Naked Eye and the Evil Twin) in the “Allston Mall”, as well as the 88 Room moving to a larger space in the same building, which isn’t noted in the article as the reporter has no idea, is not in the business of criticism or cultural documentation but in finding copy and creating an angle for The TAB’s readers, the TAB being another weekly newspaper that is no longer extant.

“Another Thing” is typical of the understated or tongue-in-cheek titles Guthrie chose for group shows, seeing as the show had an environmental or alternative energy theme; the title meant to indicate the tossed-off or sidelined aspects of environmental issues typical to policy makers, as in “oh yeah, and another thing . . .” The show continues with Davidovits’ mode as everyday or personal objects are contexualized and made into “museum exhibits”, and the viewer must discern what’s “real” and what’s a “story”.

“Another Thing” is typical of the understated or tongue-in-cheek titles Guthrie chose for group shows, seeing as the show had an environmental or alternative energy theme; the title meant to indicate the tossed-off or sidelined aspects of environmental issues typical to policy makers, as in “oh yeah, and another thing . . .” The show continues with Davidovits’ mode as everyday or personal objects are contexualized and made into “museum exhibits”, and the viewer must discern what’s “real” and what’s a “story”.

The reporter did pick up on, or accurately quote, a key aspect of the 88 Room, when Guthrie says, “I would describe the room as an artist run space, which makes all the difference”, the point being that curation was treated as a creative process in and of itself, and artistic empathy was well-established between host and whoever was invited to exhibit.

March 5 1992 Bay Windows (article by Shawn Hill) “Pillow Talk” (group show)

(for scan of the original article go here)

Somewhere along the way, Guthrie connected with Ron Platt, who was then assistant curator at M.I.T.’s List Center for the Visual Arts, a circumstance facilitated by artist Cheri Eisenberg, who was friends with both parties. In cases like this, it’s a matter of people “hitting it off”, and so a friendship developed as well as an curatorial entity that would be known as Dear Me Suz. Dear Me Suz curated three shows at the 88 Room, of which “Pillow Talk” was the first.

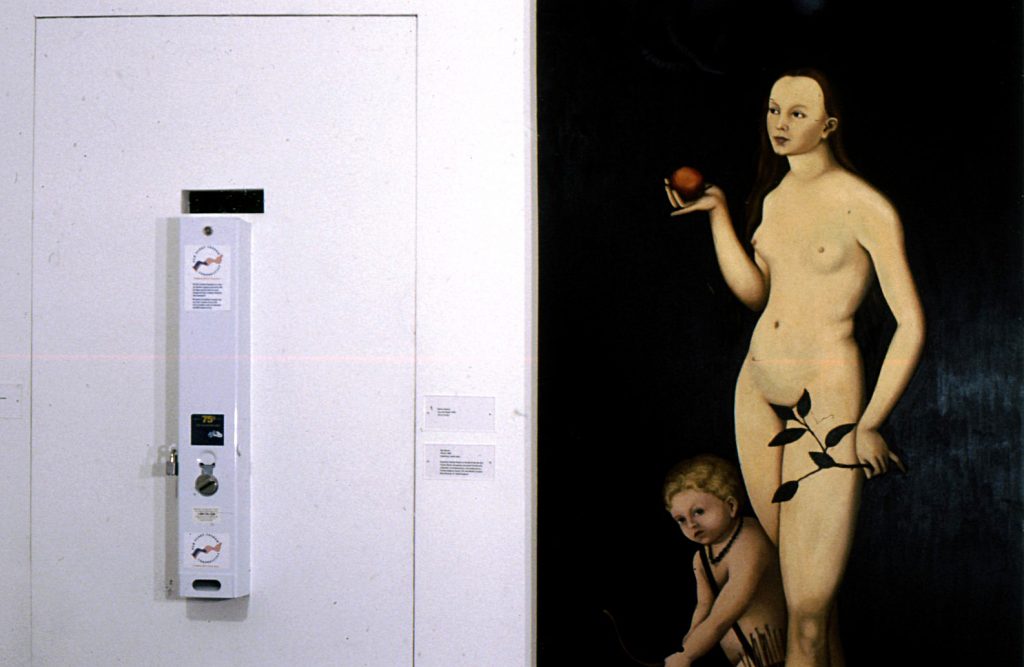

Installation shot from “Pillow Talk” with Jay Critchley’s “Old Glory” condom machine, and Nancy Jenner’s painting (for full sized image of Jenner’s painting go here)

Wikipedia describes Bay Windows as “an LGBT newspaper” which is still in existence, publishing twice a week. You can note that Shawn Hill gives the most space to artist Eric Davis’ photo montage with its gay-themed narrative, while also making Platt the headline’s focus; yet he dutifully makes sure to include Eisenberg and Guthrie in the credits (but no mention of Dear Me Suz). The biggest compliment being: “Pillow Talk is actually the more focused of the two shows (the article also reviews “Cannibal Eyes”, a group show at the List Center). Platt and Guthrie have somehow fit seven artists, each of whom works in a different medium, in this closet sized space with no feeling of claustrophobia.”

“Pillow Talk” not only included thematically-gay photography, but also a wide spectrum of sexual inclinations. For instance, a private booth posted a fill-in-the-blanks survey on onanistic habits which were then scrawled on a poster ala graffiti in a public toilet. Given that “sex sells”, “Pillow Talk” might have been the 88 Room’s most successful opening in terms of attendance, with local rock and roll celebrities also making the scene.

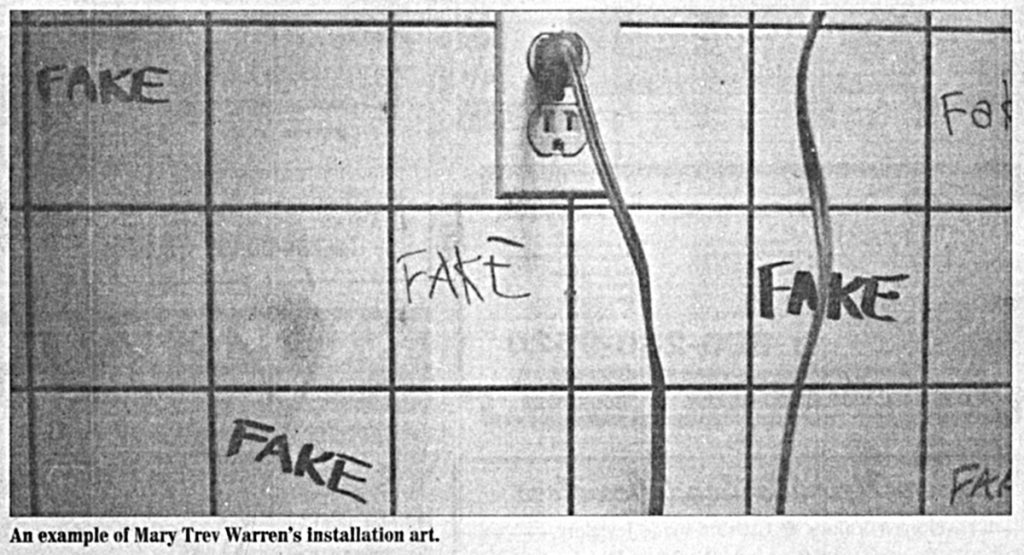

May 2 1992 The Boston Globe (article by Sally Cragin) “The Allston Mall” and “Snoop”

(for scan of the original article go here)

Here you get a complete run down of the so-called “Allston Mall” in 1992. Who coined the term or if indeed this article set it in place, who knows? What is known is that while the article states, “Before Nirvana and grunge, there was the Allston Mall. And long after Nirvana and grunge there will be the Allston Mall”, which goes straight to the article’s hyperbole, it’s mainstream attempt to pigeonhole the trendy. This was perhaps the high point of the “Allston Mall”, as by the time the 88 Room pulled up stakes in 2000, there were homeless people jimmying the downstairs door and crashing in the hallway for the night. The “Allston Mall” is long gone, and the building’s new owners no longer allow easy access to the second floor.

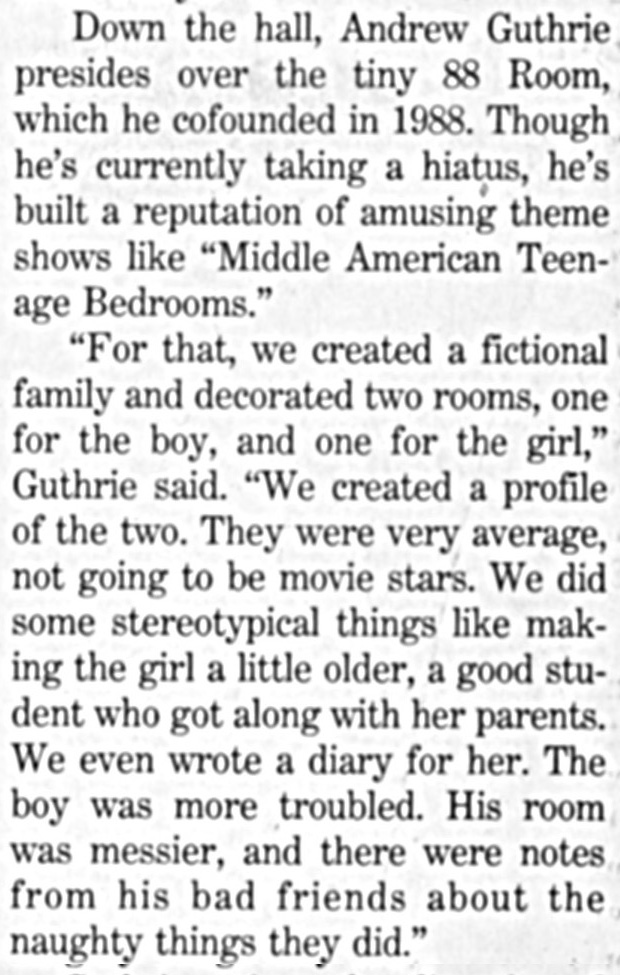

This is also the first mention of the 88 Room in The Boston Globe, Boston’s extant daily newspaper. Additionally, it contains the sole press coverage of the second exhibit by the curatorial team, Dear Me Suz (Cheri Eisenberg, Andrew Guthrie, Ron Platt) who had moved beyond curation to production, with a show titled “Snoop” (see insert from article for Guthrie’s description of the show). But wouldn’t you know it – the reporter gets the name of the show wrong, only citing the show’s sub-title. “Snoop” utiliized the space of both the 88 Room and the Evil Twin Gallery, so that each “teenager” could have their own room (there is no mention, in the article, of the Evil Twin gallery, which might mean they had already discontinued). As indicated in the title, “Snoop”, visitors could go through the two teenagers’ rooms at will.

May 22 1994 The Boston Globe (article by David Wildman) “Pairalyzed” (two-person installation) and Gary Rattigan’s flags (solo exhibition)

(for scan of the original article go here)

The two art colleges in Boston, Massachusetts College of Art (a state school) and The Museum School of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts (a private school) provided many of the artists that exhibited at the 88 Room, demonstrating the risks the 88 Room could take, or the niche it filled, as opposed to a commercial gallery or an established exhibition space like M.I.T.’s List Visual Arts Center, as well as art students being able to take the first steps out of the hermetic confines of academia. This is not to say that it was easy to find material suitable for the 88 Room at either college or by way of slogging through various open studio events.

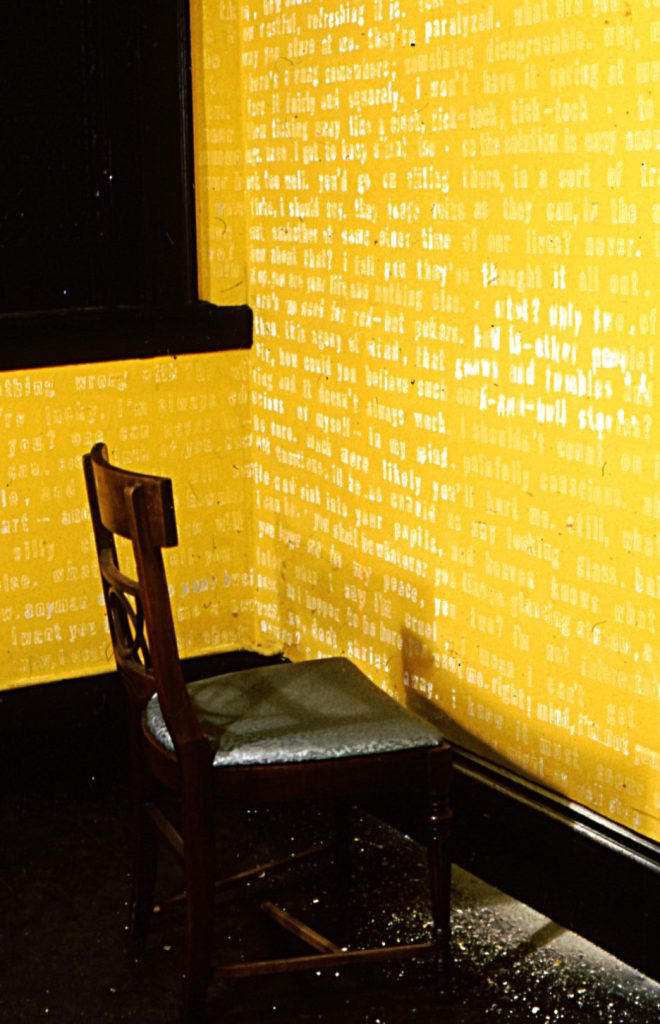

Here we find artists Kim Bush and Mark Warhall, who approached the 88 Room on their own, riding in separate but facing elevators in a Massachusetts Collage of Art building, reading Jean Paul Sartre’s iconic play “No Exit” all the while, and waiting for the moment when their individual elevators landed on the same floor at the same moment (the everyday elevator user determining which floor the elevator went to). When that happened, they snapped a photo of the person in the adjoining elevator. They did this for eight hours. Warhall says (in the article), “We thought we would meet up five of six times. We ended up meeting 49 times.” Bush adds, “It was pretty hectic sometimes and really laid back at other times.” Essentially, the piece amounts to an alternate staging of Sartre’s play, with the Bush/Warhall interminable take on the play coinciding with Sartre’s idea of a tedious, more than torturous, hell.

“Pairalyzed” was exhibited in the two smaller spaces of the 88 Room, one room holding a two-slide projector installation of the elevator photos, the other room taken up with the etched-in-the-wall text of “No Exit”. Gary Rattigan hand-stitched flags (which are hardly mentioned in the article), with their pertinent take on nationalist iconography, was shown in the larger central room. Gary Rattigan was also the publisher of the short-lived but influential arts magazine “Arts Dynamo”.

Sartre’s “No Exit” etched into one of the smaller rooms of the 88 Room. This text is probably still buried beneath whatever layers of plaster/paint have since been applied.

February 13 1995 The Boston Phoenix (article by “MA”) “24 Hours of Video” (group show)

(for scan of the original article go here)

These 24 hours of video were split into two weekend days, running from noon to midnight on Saturday and Sunday, the full title of the event being: “24-hour Recreation of Television Programming by the Local Idea Council”. Owner/Operator of the 88 Room, Andrew Guthrie (who videographer and curator George Fifield, R.I.P., once referred to as the factotum of the 88 Room) had legally incorporated as a non-profit under the name of the Local Idea Council, Inc., a moniker which would evolve into LikInk (www.likink.com, where this blog is located).

This was, as has been previously stated, the nascent period of the internet. At this time, the 88 Room could not effectively promote its events on the internet, or program a similar event on something like YouTube. This was a period where video art perhaps held the spot that internet or web art would hold in the coming years, that would be – an accessible, relatively inexpensive art form that was generally refused or neglected by “the art world” and/or commercial galleries. There was cable TV’s community channels, which in effect “24 Hours of Video” mimics in this low-budget and community-oriented method of distribution.

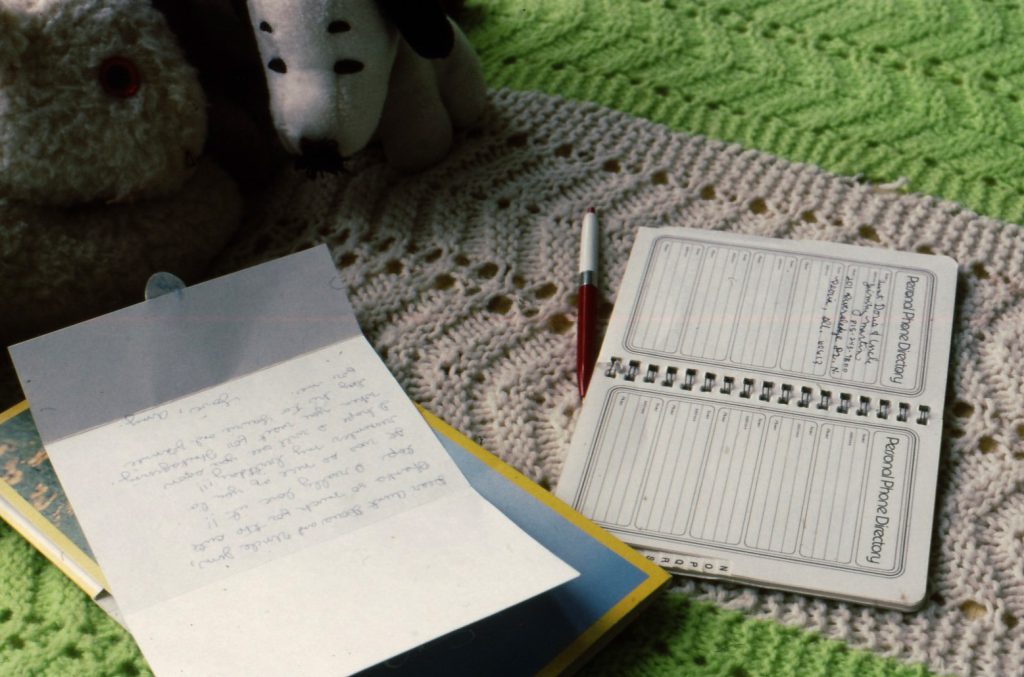

January 16 1996 The Boston Globe (article by David Wildman) Mary Trev Warren (solo installation)

(for scan of the original article go here)

What the 88 Room looked for in an artist’s work, fundamentally, was the use of non-traditional materials or a non-traditional method of making art. There is a vagueness to the term “non-traditional”, seeing as the opening up of the conditions or requirements of art had been going on for 50, if not 100 years. In the 88 Room era, the term or genre “conceptual art” had come into vogue, the genre as posited, for example, by artists in 1960/70s New York City. The 88 Room itself followed this mode by being an “alternative exhibition space”, by staging thematic group shows, by inviting independent curators to organize shows.

Solo artists shown at the 88 Room landed in the “installation artist” bracket, effectively curating the space as a space, using it as a canvas (to use traditional terms). But as you can note in the article’s quotes by Mary Trev Warren, in her case, the shift was very, very subtle, intriguing. What attracted the 88 Room was the daring quality Mary Trev Warren’s work, the way she refused all or most materials except what was directly at hand (the space) and that her gestures were so slight as to be practically invisible, just as we walk by significant events or spaces each and everyday without noticing a thing.

This act of disappearance had nature cooperating as Mary Trev Warren’s opening was the only 88 Room opening that was cancelled, that had to be cancelled, due to a massive blizzard that arrived on that evening. Continuing along that line, the 88 Room unfortunately has no installation photos of her exhibition.

February 25 and March 14 1996 The Boston Globe (articles by David Wildman and Cate McQuaid) “Hippie” (group show)

(for scan of the original David Wildman article go here, for Cate McQuaid article go here)

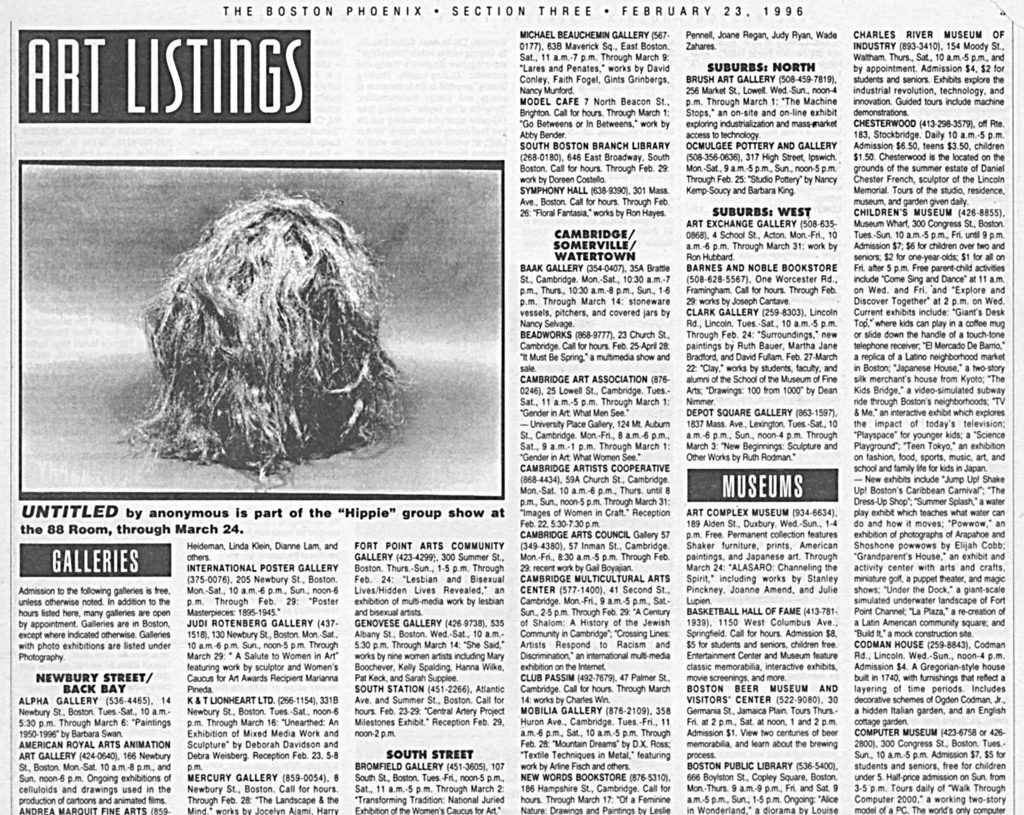

This time, it’s worth posting (rather than linking) the entire listing page of The Boston Phoenix as they printed the anonymously-made photo of a wig that was used to publicize “Hippie”, which wasn’t actually included in the show. It’s sole purpose was to be used as publicity, and so it hit its target by leading The Boston Phoenix’s arts listings page. You also get a good sense, from the listings page, of Boston’s art scene at that time.

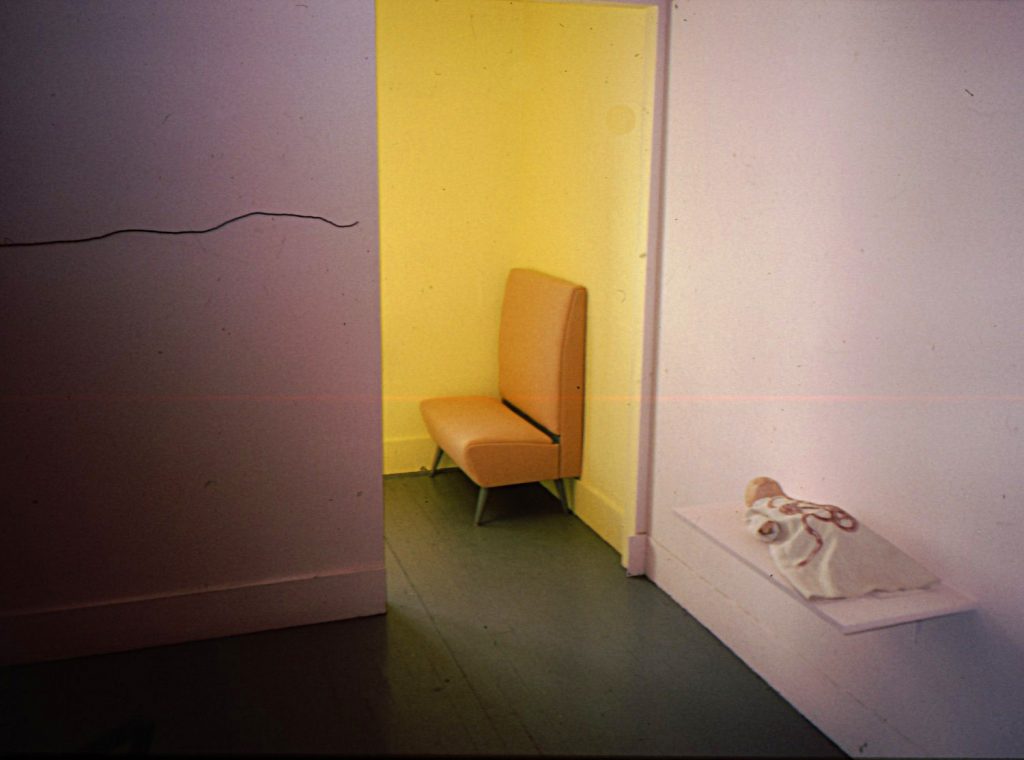

“Hippie” was a group show that included 12 unnamed artists, artists who had shown in one or another show at the 88 Room, in certain cases exhibiting some of the same work, but in this case all work was displayed without credit or explanation. The walls of the 88 Room were painted in appropriately vibrant colors for the exhibition.

It goes to the camaraderie and social axis of the 88 Room, that all artists willingly contributed to a show that stripped their work of any careerist possibility. Wildman’s article (as opposed to McQuiad’s) gets more to the point, gets into the swing of things, by interviewing and quoting more than one of the artists, while assigning an anonymous moniker to the speaker (quote): “The whole idea of anonymity was a big part of the original movement . . . says Artist Y . . . we didn’t have leaders, and only knew people by their first names . . . the side of hippie culture that is very much anti-consumerist”. The director/curator himself, who posited the concept and title of the show as a tongue-in-cheek undertaking, is reduced to his initials, making a pertinent comment that moves beyond the mere hippie: “Besides, the way conditions are in Boston a list of local artists’ names doesn’t mean much anyhow”.

David Wildman was what’s called, in journalism, a “stringer”, while Cate McQuaid was the regular (and might still be) arts reviewer for The Boston Globe. To get a review in The Boston Globe was about as big time as an artist/gallery might hope to go as far as a local media coverage that was wide-spread and pervasive. Wildman showed his fidelity to the 88 Room by making this his third review, while this was McQuiad’s first, one and only, review. Not only that, but she feels the need to out (to identify) one of the anonymous artists, a conceptual misstep which coincides with her curious comment about one of the other pieces “It’s goofy, it’s annoying, it’s hip”.

The outed artist’s piece (on right) as well as the anonymously-presented line of black tacks (on left) from the “Hippie” show

April 3 1997 Bay Windows (article by Shawn Hill) December 23 1997 The TAB “All for One/One for All” (group show curated by Ana de Azcárate)

(for scan of the original Bay Windows article go here / for scan of the original TAB article go here)

This show ends the round-up of print media articles that the 88 Room received in its ten-year run. Ten years is a long time for an under-financed, under-staffed and hardly-reported-on exhibition space to exist, and admittedly, the director Andrew Guthrie was burning out. Therefore, at this point, the new blood that Ana de Azcárate provided, as independent curator of “All for One/One for All”, was more than welcome. Ana de Azcárate (who goes unmentioned in the article, unless you count the contact information at the end) was put in touch with Guthrie via Ron Platt (cited in the above articles concerning “Pillow Talk” and “Snoop’), and apropos 88 Room’s praxis, de Azcárate not only curated the show but widened the social circles and established friendships that truly amounted to the 88 Room’s signifiant but non-monetary compensation.

It’s also heartening that the review is so extensive and positive, with Shawn Hill stating (among other things), “88 Room is a vital space in the city, an interesting site for some members of alternative culture and some more daring art world figures to bring challenging, new artists to Boston (not to mention focusing attention of unknowns already here). In a city not know for consistent arts funding . . . it’s an oasis of innovation and fun”. Yes! Fun!

But what’s doubly-amusing is “All for One/One for All” turning up in The TAB’s year-end review of Boston’s 1997 art shows, landing at number six, sandwiched between a Picasso exhibition and a well-established commercial gallery’s photography exhibition.

And it should also be mentioned . . . .

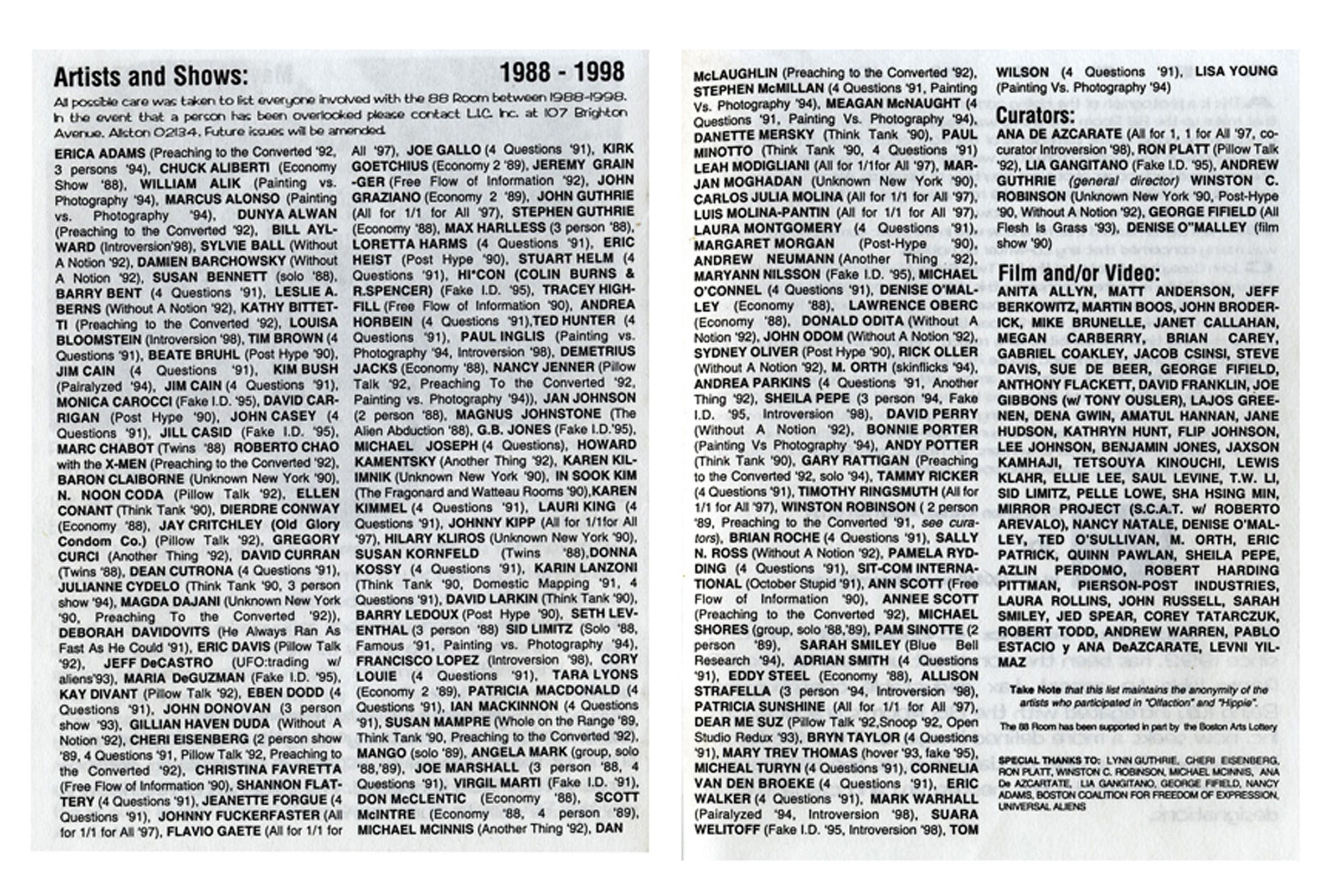

. . . that this print media archive leaves out many, if not most, of the exhibited artists and exhibitions shown at the 88 Room, being dependant, as it is, on the vagaries of journalism and arts criticism. To that end, somewhere around 2000 a small, self-published zine was made detailing the 88 Room that includes most of the above, plus some more. You can find a PDF of that zine here. What will be excerpted (below) is a listing (from the back of the zine) that lists ALL exhibited artists, the shows they were in, as well as curators and any person who provided integral support to the 88 Room.